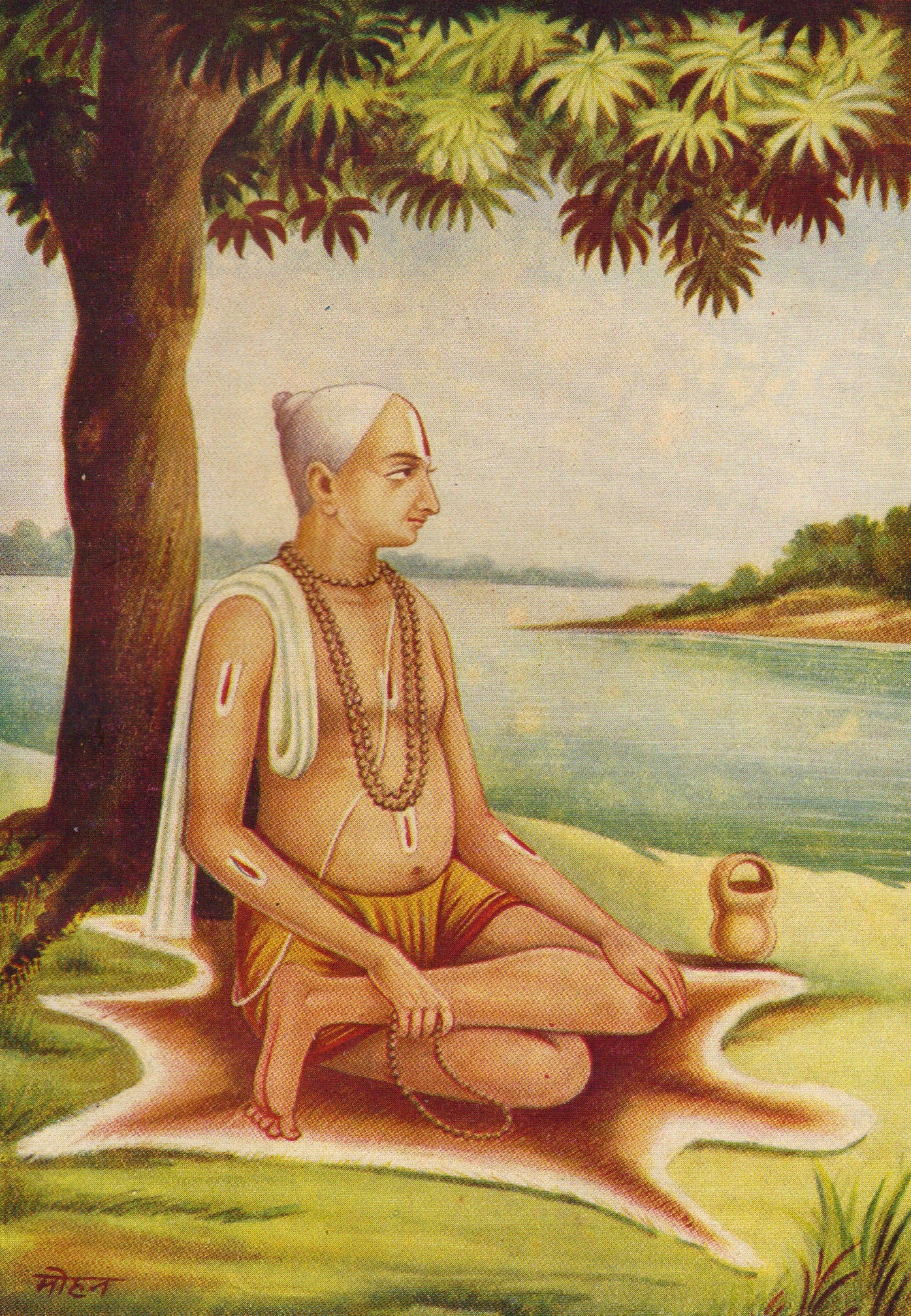

Illustration 1: Goswami Tulsidas, the 16th century Hindi poet, whose abridged version of Ramayana, cut down to its essentials, played an important role in the cultural adaptation of the Epic in Northern India in the late Medieval/Early Modern Era.

Source: Personal copy of book Ramcharitmanas, published by Sri Ganga Publishers, Gai Ghat, Benaras, 1949

This is the sixth part of my reading reviews for 2024 (Read the fifth part here). The books here are breezy reads - 200-300 pages, large font, ed/op-ed quality musings - that you can graze through in flight mode, especially if you are trying to avoid brain rot. The first is a collection of essays by a contemporary historian who I have highly regarded, and whose committed, centrist stand has made him a target of both the left and the right. The other is a true “Everyman’s Classic” - a book written by someone whose ability to filter down complex concepts of behavioral finance into a doer’s manual will leave a bigger legacy than people infinitely smarter than him.

Illustration 2: Francois Marie-Arouet, better known as Voltaire, widely considered as the first liberal scholar. Source: D'après Nicolas de Largillière, portrait de Voltaire (Institut et Musée Voltaire)

I don’t remember when I bought Patriots and Partisans. Most likely I didn’t. I might have picked it up from the communal bookshelf at home. Well, communal in the sense that it belonged to everyone at home, not the way it is often understood in contemporary times. I suspect it was bought by my elder brother trying to read something at the airport. Which is where it fits. A mildly entertaining collection of flash cards of key events and ideas from post Independence India. Quite quotable. And something that refrains from inducing any kind of intense emotions - especially the negative ones - in the reader. It is a perfect book to read when you are in flight mode.

However, even a flash card deck of liberal concepts has its value. Especially in a time, when our ways of reading have begun to slowly mirror the algorithms that select for us what to read. In the sense that we first tag and meta-tag each text subconsciously, trying to label the author into ideological clusters - “post colonial”, “alt right”, “bleeding heart liberal”, “natalist”, “apologist” and others, and only then begin to process what is said.

In a country divided along the salients of caste, region, religion and language, few things are easy- and thanks to AI, becoming easier - than to interpret the world from a biased lens. A lens tinted by the experiences of your own religion, caste, linguistic group or economic class. Your side is chosen; your friends and social media clan affirm your convictions every time you challenge someone different from you.

The challenge with being a liberal is that your only fidelity is to an open debate. Not to any player as such but to the umpires and referees of the game. That is where it gets difficult - especially when everyone suspects you of being partial to the other side. Of umpires being compromised. Being liberal, in this metaphor, is to be terribly lonely. To be wedded to rules, not ideas and teams. This book is an affirmation of that trait. That is what makes it so important as a collection of essays on post Independence India.

In certain emerging media circles Guha is understood as a champion of Nehruvianism, of obsolete ethics that pulled back this country’s rise and obsessed themselves with giving a voice and platform to everyone that is a part of this republic. But that stems from a selective reading of his work.

This book has something to offend everyone -whether you are a Conservative nationalist, or a Bharatiya Neo-Con, or a Nehruvian socialist or a hard leftist. Compiling this essay in the last days of UPA II, Guha accurately identifies the problematic traits in Congress that would lead its exile to power, and likely complete irrelevance in the coming years.

He identifies how the suppression of intra-party democracy that began in the Indira Gandhi years (importantly not in the times of Nehru and Shastri), led to an organizational structure where your worth and prospects were wholly determined by your distance from the First Family. At the time of this book’s writing, Congress looked like the court at the Red Keep in George RR Martin’s novels - brilliant on tactics to keep itself in power, bankrupt in vision for the country. This critique is important, considering that Guha himself identifies with the center left, where Congress was initially positioned before it unmoored itself of all ideological anchors.

He is equally unsparing to the Left. As someone from industrialized eastern India, which leftist movements had a significant political following, I chuckled with schadenfreude quite often, while reading his essay “ The past and future of Indian Left”. He lays out in detail their obsession with ideas and visions which don’t have any relevance for the poorest of Indians today. He especially singles out the leftist governments of West Bengal in the last quarter of the 20th century, which successfully kicked down a prosperous and industrialized state and contributed to ideas and incentive structures which have kept it there since.

The opposition to English education, to digitization of offices, and to any form of modernization by the government could only have come from a people who had never spent a day doing a job, either because they were too rich to bother with one, or because they had a degree that would make them unemployable, unless they banded up with losers and grumblers.

Though this book predates the rise of the now ascendant Nationalist right, it does provide a well-argued prescription of some basic rules that have kept this country together, in the face of strongly held convictions of Western political scientists.

First, that the enduring changes in this country have been brought by grassroot reform, and not “mass mobilization” a la Maoist China.

Second, it cautions against the deification of a particular political leader, which typically precedes the destruction of intra-party democracy and later a complete loss of legitimacy by the party (as it has unfolded for Congress). It bats for impersonal, inclusive and rule bound institutions as the source of power.

Third, it advocates a mentality that accepts the plurality of India. The fact that there is some truth in all perspectives. That there is no wisdom in the erasure of any strand of what makes us a country. Of course, this prescription places him right in the crosshairs of ideologues of both left and right (and especially right) incentivised to label people and discredit their ideas as bad faith arguments. But that, as I mentioned earlier, is the risk that any fanatical liberal must run.

The second part of this book, which comprises essays on libraries, magazines, publishers and portraits of intellectuals, while intensely enjoyable, was at the same time very foreign to me. For someone who grew up in an exurb of a Tier-3 city in India, studying in an English medium school, the contrasts with the growing years of the author, whose political leanings I strongly identify with, were extremely stark.

Is an appreciation for tolerance, of rules of law, and towards reform and pluralism, something I have imbibed because it provides a cogent narrative to my journey as a citizen of this nation? Or is it something I have adopted to become more palatable and liked by the intellectual elite of this country like the author, who were more fortunate and well-provided in their upbringing than me in their formative years? I will never know. But isn’t scepticism and a healthy amount of self-doubt on one’s own strongly held beliefs itself an incentive enough to nurture a rules-based order?

This book is nothing like “India After Gandhi” or “Gandhi Before India” - two works that have cemented Guha’s reputation as a pre-eminent historian of contemporary India. That said, in a world where it becomes increasingly difficult to locate anything on the web more than 2 years old, without running into a paywall or a badly designed web page teeming with ads, having all his essays written in dozens of magazines over decades, is a good way to pay your tribute to any author whose ideas you strongly identify with.

Illustration 3: Among Finance writers, Morgan Housel is like Coca Cola - a brand whose power and perception is independent of its consumers. It has something valuable to tell the learned behavioral economist as well as the high school entrant.

Source: Wikipedia

I read “The Psychology of Money” in a single night. This book was a gift to us by the co-founder of a start-up that I used to work in, following a corporate retreat. Now, the books they give you at such retreats tend to have a very unhealthy reputation, especially among readers of long reviews like this one. They are supposed to be a cliched, bullet-point list of the obvious. They are meant for mention by corporate celebrities in their “must-read” lists on social media - possibly one in a list of 50-100 books they “read” every year. In short, books which fall in this category are considered quotable but shallow. The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel is not that book. It is an Everyman’s Classic.

A senior at work, a few months ago, gave me a great example of brand power - Coca Cola. You don’t perceive a bottle of Coke any differently whether it is in the hands of a security guard outside your building or the President of the US. Its value is independent of specific associations. In my mind, this book occupies that same place.

You will find it both at the table of a high school student trying to make their first acquaintance with the world of money, and an investment advisor at a Multi Family Office dealing with millionaire clients. Coke connected with people as a symbol of American consumer culture, of which the President and the worker were both a part. This book connects similarly with people. By telling them that money is not something to be left to financiers. By laying out a practical path to doing the best with money in life. It is a symbol of democratization of financial literacy.

For anyone in my place, having spent 10+ years in the financial services industry, the lessons in the book are nothing new - though some examples here and there may be. But here is the thing about finance - its lessons are mostly intuitive to understand, but difficult to put in practice. It is unlike subjects like quantum physics or Nano chemistry, which while important to humanity, don’t require any level of expertise from an average human. Finance isn’t that subject.

We interact with money daily, we work for it, and we use it to buy time. And as Housel emphasizes time and again in this book, it isn’t about the numbers - it is about the psychology - where emotions get involved with money. Because of its ubiquity and the emotional intensity with which it interacts with our life, the lessons of finance, even when obvious, need to be repeated and reflected on. This book excels there. It breaks all the deep wisdom of Buffett, Munger and Kahnemann into practicable rules for life.

If the former are like Valmiki and Bhavabhuti of the Ramayana tradition, Housel is like Goswami Tulsidas. Like Tulsidas’ Ramayana, his lessons in finance are also more likely to resonate culturally than those of more esoteric scholars.

One lesson that I found worth remembering from this book was this - pessimism and sensationalism sells in the world of investing. The point is not to time the markets and to trust the process of saving and investing. That said, all of this must be understood with the caveat that these principles work for a country with stable financial institutions, where the faith in the central bank’s ability to preserve the value of currency is robust.

What it also helped me understand is this - “I want to be rich” is a subjective statement. Beyond a minimum subsistence level of income, what we want out of life can differ - and hence we should look to save and build for that outcome. This is another message that is lost in any generic financial advice that you would see in the media. Housel’s emphasis on personal context when it comes to making decisions about investing and risk are another aspect that makes this book referrable.

A criticism that I have heard of this book is that - it doesn’t tell me what to invest in? But asking that question is like wondering why Premchand doesn’t write spy thrillers. It is not a book about investments, it is about developing some healthy habits when you look at opportunities to make money. Yes, the examples and illustrations are largely focused around the US. It is also true that a lot of fund managers and corporate strategy teams have done disastrously by applying the lessons from American business and finance literature to their local context. Well, if you are smart enough to notice that caveat, then you should be smart enough to seek a book/ write one adapted to your local context.

By the end of this decade, there’s the expectation that AI will commoditize knowledge discovery and summarization. Children in school will need less and less assistance to know the facts of a subject - formulae, proofs, historical dates, geographical features. The emphasis of education will shift to living a better life, being prepared for a world where change and trajectory of work life is much more kinetic than today. Education will be about acknowledging impulses, and learning to act on them. Financial, Legal, Civic, Relational literacy will matter more than number and factual skills. The Psychology of Money is the first book meant for that age. I will not be surprised if you see it as a recommended read for every teenager who starts their relationship with money.

If you want gift ideas for young people, give them this book.

The next part of this essay will review two books. One, a satisfying primer on Emerging Markets, that has lost some of its shine with time. The other, is another one by Tolstoy, where he unknowingly tackles - “burnout” and “authenticity” in life, making it an unanticipated sermon from a great great ancestor to Millennials and Gen Z.