How India Invests

Are investors in some states less risk averse than the others? Some original research into what makes investors in some states put more money in equities and less in term deposits

Anthony Soprano giving the age-old, useless advice on buying land to his son; Credits: HBO

Prologue

Sopranos: Season 4, Episode 7: Watching Too Much Television

Mob boss Tony Soprano drives into Newark with his son AJ.

Fall 2002. The Dotcom Crash is a recent memory and the markets are down nearly 78% from their peaks around 19 months ago. At this time, people often pull out investment wisdom from the 1930s, and apply it , sans context, to the financial realities of the early 21st century.

After having recounted an anecdote about his grandfather, who was an Italian immigrant in the town in the 1920s, Tony looks outside and remarks - “Buy Land AJ, because they ain’t making any more of it”. That wisdom seems like a Tethered Cat when uttered. This is 2002 after all! We are in the immediate aftermath of one of the strongest equity bull markets that America had seen in the 1990s.

It might have been wrong in 2002. But it was not misleading if you were in the 1920s. What Tony was doing was parroting a solid investment strategy for a Catholic, working class immigrant from Italy into the US in the early part of the 20th century. Someone like his grandfather. Someone who had limited legal residential documentation, no source of regular income and a scant access to information about money and investments. Buying land, through legal and illegal means, and holding it till parts of New Jersey gentrified - was a surefire way to generate a surplus.

If you met someone living in those times and circumstances and tried to convince them to put their money in equities or mutual funds-investments- which would both handily beat real estate in the next thirty years- you would meet a lot of deaf ears.

No one is foolish

This importance of existential priors - one’s own lived experiences - on investment choices and risk appetites isn’t just tangentially anecdotal. Morgan Housel, in his everyman’s classic “Psychology of Money” alludes to this in his opening chapter too.

In a research for NBER in 2009, Ulrike Malmedier and Stefan Nagel showed how people’s personal experiences impacted their investment behavior. They do it either by changing their preference for risk or by changing their beliefs about the world.

People who had come of age and begun investing in high inflation periods ended up having a higher propensity to park their savings in cash. On the other hand, those who started their journey when equity markets persistently outperformed bonds had a tendency to take higher risks, stick around longer and invest a greater portion of their savings in riskier asset classes. Ergo, Data is not just plain Data when it comes to investing. Personal experiences matter

And there is such a thing as a reference point when it comes to default investment behavior

It is not just the market conditions of the past that determine investment choices. Income expectations do as well. Entering the job market during recessions is directly linked to overall lifetime income losses (between 5-20%), limited career mobility and hence a lower cushion for risk-taking (NBER 2006). These lower future income expectations, in turn, translate into a lesser propensity to take risks.

Much of this comes down to Reference Dependence, a concept closely related to Kahnemann’s Prospect Theory. Even though the risks of investing in an asset class might be the same for two investors - A and B, they may have different expectations of future income. If A expects a higher income in the future, their reference point would be more optimistic - inducing them to take a higher risk and over-allocate towards riskier assets than B.

Do States and Economic Regions think and behave like individual investors too?

So much for people. Imperfect decision makers, carrying the generational biases of markets in which they came of age and influenced by their own prospects of non-investment earnings. The next question to ask is - does this apply to societies, states and countries as well?

This essay is based on my attempts to do so.

As Isaac Asimov speculated half a century ago, and as big data and analytics is validating - social groups also have personalities. These are shaped by common beliefs, political systems, economic conditions and narratives of past economic successes and failures. The larger these groups get, the lower the possibility of outliers and greater the chance that you can predict and test the patterns in investment behavior.

Now, let us get on to more serious stuff…

I take 21 states of India (and Delhi) which have a population greater than 25 million. Then I try to explore if these states too have investor personalities.

How does their allocation to Equities, Term Deposits and Gold vary, when adjusted for income effects?

Are some states more geared towards riskier investments than others?

What explains this behavior? And is there a comparable case study outside India?

I first divide the states in my dataset into five buckets.

Convergent States: GDP per Capita < National Average; Growth in GDP > National Average (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, Rajasthan, Odisha)

Laggard States: GDP per Capita < National Average; Growth in GDP < National Average (Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal)

Rich Southern States: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Kerala, Tamil Nadu

Outliers: These are highly urbanized states and/or legacy financial centers. Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat

Rich Northern States: Punjab, Haryana

How do we compare the investment appetite of states for different asset classes?

I consider four kinds of assets:

Direct Equity holdings: As proxied by equity market investors per 1000 people by state

Equity Mutual Fund Investments: As proxied by AUM per capita by state

Term Deposits: Average retail term deposits

Gold: Average gold holdings per household

Who loves risky stuff?

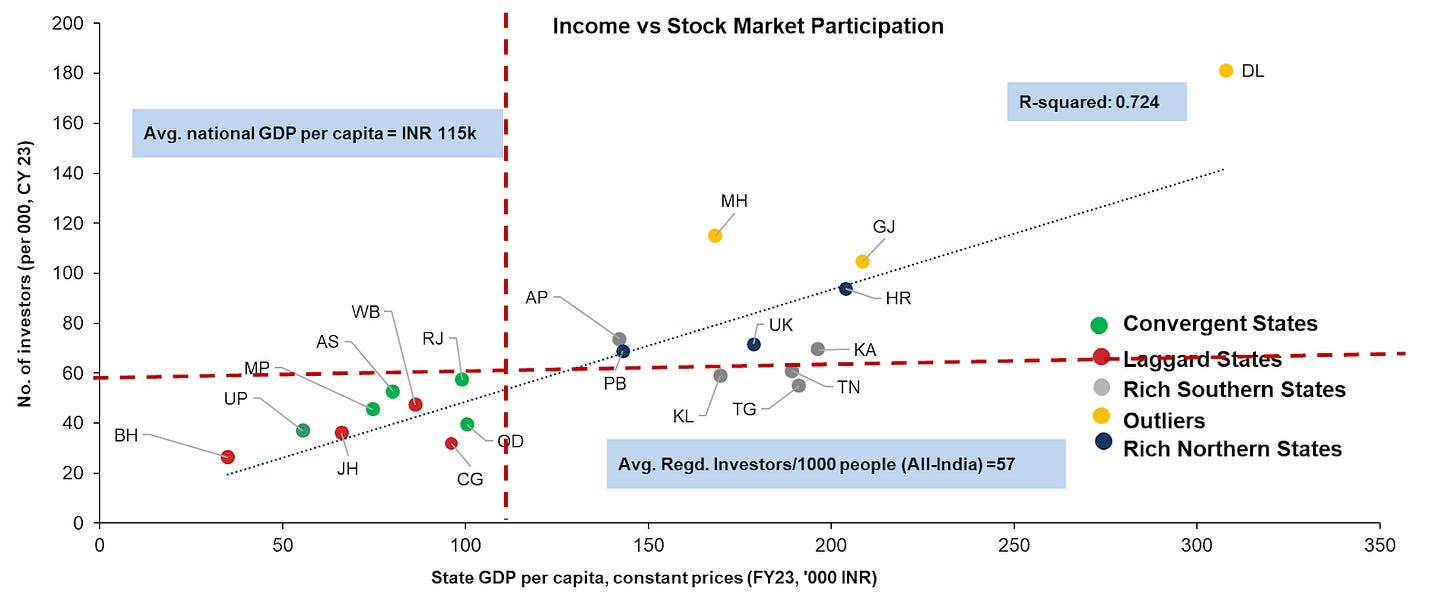

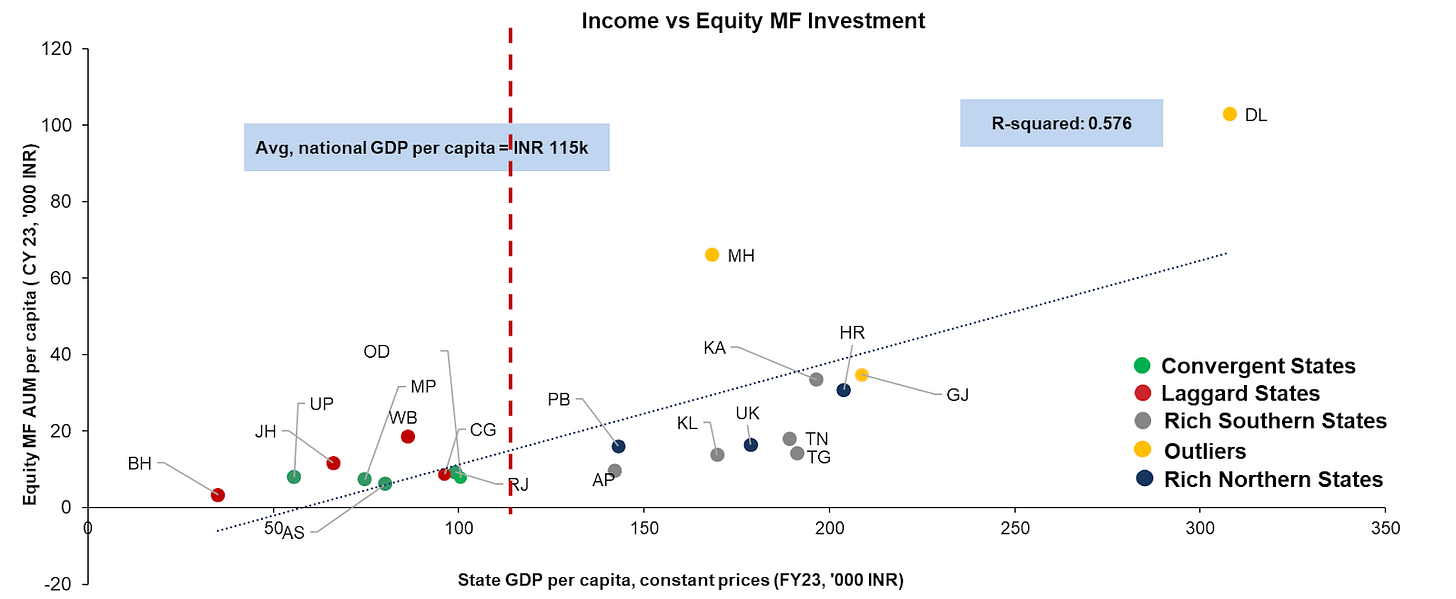

Indicators of investment appetite, as proxied above, are comparable across states only if we take into account the differences in income levels between them. The next two charts show the first two of these metrics regressed against State GDP per Capita.

Illustration 1: As with other Emerging Markets*, participation in stock markets is positively related to income levels; Source: NSE Market Pulse, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Reserve Bank of India, MOSPI, * Zingales and Guiso (2008), Wolff (2007), Klapper and Panos (2011)

Illustration 2: Equity MF AUM per capita also tracks these broader macro trends by state in the same manner, albeit weakly; Source: NSE Market Pulse, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, AMFI, MOSPI, RBI

There is a clear message at the first glance when you look at these charts - the richer a state, the greater the participation and investment in risky assets (equities and equity mutual funds). But there is much more beyond the obvious. And also precisely the reason why I introduced the bucketing of states earlier in this essay

The fun begins when we start looking at the outliers to the regression line in these two charts

The True Outliers

Delhi (DL) and Maharashtra (MH) lie far above the curve. Which is not surprising given that 3 of the top 5 regions in terms of the number of investors (Delhi-NCR, Mumbai and Pune) lie in these states. Furthermore, while the numbers for other states are attenuated by rural areas, where familiarity with financial investments is lower, that is not so with Delhi. NCT of Delhi has a 92% urban population (~3x national average) and a GDP per capita >2.5x that of the country

Risk Hai to Ishq Hai

The next to catch the eye is Gujarat (GJ). A state where equity market holdings are significantly above the line relative to its income levels. But amusingly enough, it is also a state that invests slightly less, relative to its income levels, into equity mutual funds. One part of the puzzle can be verified. Ahmedabad is the second largest city in terms of equity market turnover in the cash segment (after Mumbai). It outranks Delhi, Kolkata, Hyderabad and Bengaluru. Other cities, much smaller in population terms - Rajkot and Vadodara- also make up the top 20 list on the same parameter. Does that translate into a (relatively) lower propensity to park their funds into equity mutual funds for people in this state?

Risk, yeah? But everything looks good in limits, no?

Now let us look at the gray and blue dots in the charts above. Nearly all the Rich Southern and Northern States, relative to their income, lie below the line - whether you look at equity market holdings or equity MF investments. Kerala (KL), Tamil Nadu (TN), Haryana (HR) and Telangana (TG) seem to be significant undershooters, when it comes to the investors’ appetite in these states towards risky assets

We have nothing to lose but our own fears

Convergent States (all in the North) present another interesting aspect. Specifically, Convergent States like Uttar Pradesh (UP), Madhya Pradesh (MP), Assam (AS) and Rajasthan (RJ) are all over-indexed relative to their income levels, when it comes to equity investments (direct as well as through MF route). Odisha (OD) seems to be an outlier, remaining under-indexed relative to both types of risky assets.

Outliers Flipped?

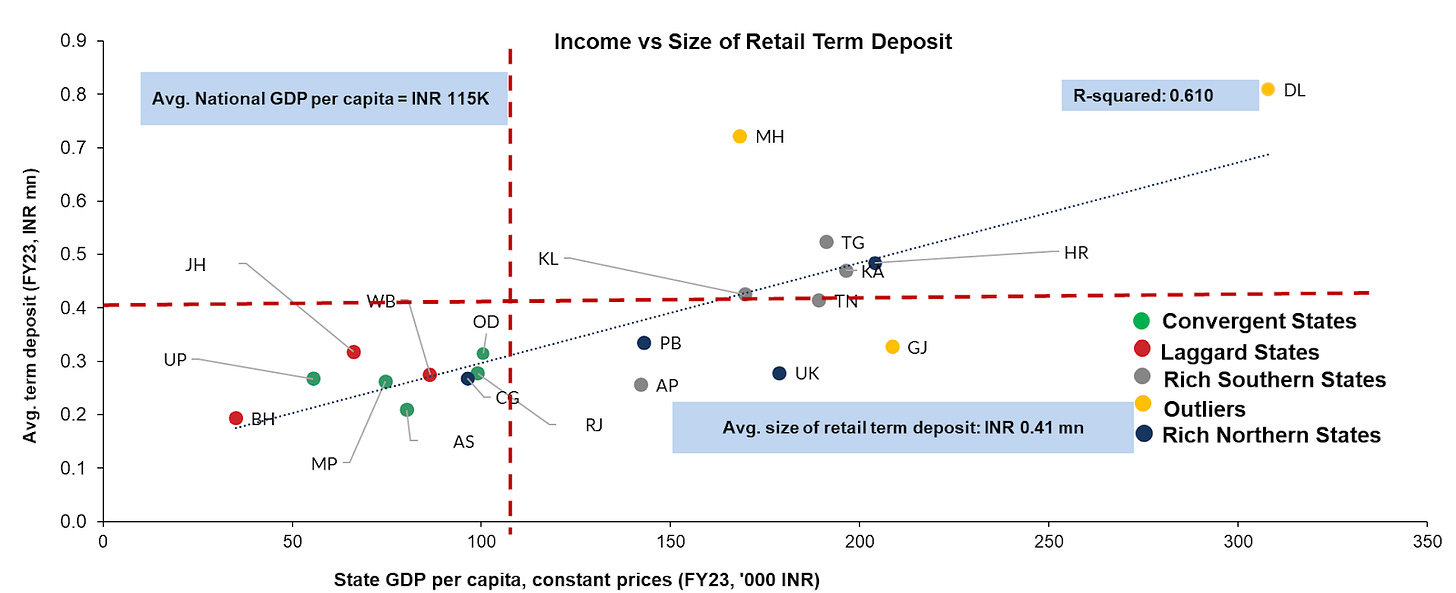

Now let us move from the higher risk part of the investment spectrum to lower risk (term deposits) to defensive (Gold) investments and see how the same states stack up.

Illustration 3: Avg. retail term deposit size has grown at an 8.5% CAGR since 2019, Equity MF AUM growth >2x that rate; Source: RBI, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, MOSPI

Illustration 4: Southern states got richer before equity markets democratized; is that why they hold so much gold?; Source: NSSO, Census, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, MOSPI, Author’s estimates extrapolating the NSSO numbers

Return of Capital, give me that

Now, when you look at Average retail term deposits by state and then adjust it against state-wise income levels, it seems that the situation of outliers is slightly flipped. Rich Southern States don’t seem to be as under-allocated towards term deposits (adjusted for income) as they were for equities (except for Andhra Pradesh).

Term Deposits? We don’t do that here

There are some states for whom Term Deposits and Equities seem to be perfect investment substitutes for each other - Rajasthan (RJ) and Gujarat (GJ). They are almost as over-allocated given their income levels towards equities as they are under-allocated towards term deposits

I will have one of everything

But this dynamic is not true for all the states. Convergent States, especially Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Madhya Pradesh (MP) are over-allocated, given their income levels, for both equities and term deposits. In my view, it might just be because we are measuring only financial savings here. And these two states in general might have a higher share of their wealth in financial savings (given their income level) than other states.

We are the Goldbugs

Holdings in gold provide another reason for why Rich Southern States and some others (Chhattisgarh) seem to show such under-allocation towards equity investments (in case of Chhattisgarh all financial investments). Three of the five top states with the highest gold holdings per household are in the Rich Southern States cohort (Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana). In contrast, average gold holdings of Convergent States (green bars in illustration 4), at INR 16K per household are nearly 50% lower than the national average

I have nothing to lose. Like literally

Jharkhand (JH), the state with lowest gold holdings per household, also stands out. It is also one of the Laggard States with an over-allocation, relative to its income levels, into term deposits and equities. Might a lack of savings in gold and land (given its poor arability) mean that a good share of it gets plowed back into financial savings?

We are buying land Tony, at least in Punjab

On the opposite end of the spectrum relative to Jharkhand, lie Punjab (PB) and Andhra Pradesh (AP). They seem to be under-indexed, relative to income, for all types of financial investments. While a consolidated account of landholdings across states remains un-measured, the size of agricultural landholdings might give a hint - about where else investments could go. Does agricultural land in Punjab, with an average holding being 3.5x the size of national average, provide an alternative channel to sequester investments? Especially if you consider its above average yield relative to the country and its history of agricultural excellence through centuries? Andhra Pradesh (AP) remains an enigma though. Its under-indexation, relative to income, persists - whether you look at direct equity holdings, equity MFs, term deposits, gold or agricultural land

The Upshot

All these insights can be distilled into two big stories.

States with higher than average GDP growth, but lower income per capita compared to the country might have a higher risk appetite. Either driven by a more optimistic view of the past, or because they came of age in an equity market with no major downturns and an unprecedented access to low cost broking

And

The inherent conservatism of Rich Southern and Northern States towards investing might come from their past experiences. Some of them remain wedded to assets and economic models that worked for them in the past (e.g. Punjab). Others (especially the Rich Southern States) might have grown rich before equity markets in India widened and deepened. Until around the mid 2000s, equity markets in India - for over a century- had been afflicted by poor corporate governance and insider trading. This might explain the instinct of those who got rich in that era to allocate more towards safer investments that offered a surety of return of capital (term deposits and gold)

India in the 2020s: US in the 1950s?

Interestingly enough, this trend is not exclusive to India. To understand why, let us go back to the United States of the 1950s. Hat tip to my friend James Rogan Quinn for having directed me to some sources that inform this part of the essay.

In his book , The Rise and Fall of American Growth, American economist Robert J Gordon talks about the emergence of the American Midwest as an engine of growth, towards the turn of the 20th century. It was in this period when Midwestern states such as Pennsylvania, Indiana, Illinois and Ohio saw the emergence of global giants, particularly in industries such as agricultural machinery (John Deere), food processing and FMCG space (P&G). Through the first half of the 20th century, and particularly in post war America, the income levels in the states were playing a sharp catch-up with those in the states on the East and West Coast.

Illustration 5: In the mid 20th century US, “convergent states” – outside the East and West Coast, saw a faster growth in brokerage offices. Might we be seeing similar trends in the “convergent states” like UP, MP Assam and Rajasthan?; Source: Joe Nocera (Time Magazine, December 1998); Gordon (2016) ; SEC, US Census Department, Motley Fool, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

Joe Nocera, writing for the Time Magazine in 1998, talks about how Charles E Merrill, noticed this opportunity. Rising prosperity in the American midwest could help investors in these states leapfrog the states on the East Coast in equity market participation. He saw an opportunity to build a strong retail broking franchise in these regions.

His trick was to set up a brokerage on wheels - offering seminars across village and county fairs, educating couples about investing together (even providing child care during these talks) and tempering the psychological and operational barriers to investing in stocks.

Between mid-1940s until 1960, Convergent State analogues in America saw a faster growth in brokerage offices and clients than more prosperous eastern states such as Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Jersey. In Merrill’s own words, rich people in the Convergent States were more likely to believe in equity investing, as their experiences were unscarred by the losses seen by those in New York or other East Coast states in the 1929 Crash and the Great Depression

Might we be seeing a similar dynamic in India, with the newly wealthy in Convergent States being more likely to invest in equities, relative to their income levels, compared to those in the Southern States? Might a relative inexperience of never having witnessed a Harshad Mehta/Ketan Parekh style stock market scandal and the optimism of ever growing income be forcing them to take more risks and ignore Tony Soprano’s advice to his son?