Losing your touchpoints

Looking at leaders and laggards in the contactless payments space in India

“I have been an HDFC Bank client for 12+ years, and yet I had, until lately, never heard of their UPI app for contactless payments. Isn’t this strange? Banks have had this mobile banking facility built in at least for 15 years, if not more. When UPI was launched as a payment interface, they should have been great at driving the adoption of their UPI Apps. But they aren’t” - said a friend with whom I was having a casual conversation sometime ago at work.

The question is - “Why indeed?”

Banks should have had a head-start in the contactless payments race, but....

ICICI Bank first started providing mobile banking services in the country, back in 1999. It was followed by HDFC Bank and IDBI. Banks had roughly a 16-17 year headstart over UPI in enabling contactless payments. A lot of what traditional mobile banking did for payments was very similar, work-flow wise, to what UPI is enabling - identifying the credentials of the person initiating a payment, authorizing the bank to debit their account, communicating securely with the bank of the recipient and building a robust system to check and intercept payment frauds. In April 2016, the month UPI was launched, banks enabled 48.7 million mobile banking transactions, worth INR 525 billion through their native (non-UPI) apps.

Cut to today, and you hardly see anyone using anything other than PhonePe, GPay and PayTM for making contactless payments around you. Banks simply seem to have underperformed in rolling out and driving the adoption of their native UPI Apps.

I asked a few of my friends, who have worked in consulting, fintech and payments business about why UPI based payments figure so low on the priority list of banks. The common answer is- there is no money to be had facilitating such payments, especially if they are between parties who do not have a bank account with the bank . Also, since the Merchant Discount Rate (what banks charge merchants on making contactless payments possible) is zero for UPI based payments, it's just not worth anyone’s effort.

But if these explanations are correct, then why do we see a renewed effort by SBI (YONO), ICICI (iMobilePay) and HDFC (PayZapp) to push their UPI Apps in the last one year?

Maybe, the answer lies in a differentiated use case for Mobile Banking and UPI for making contactless payments. Perhaps, you would be making small payments using UPI and larger ones, with a bigger inherent risk of loss, using mobile banking? That seems to have been the experience of a lot of respondents in the early years of the rollout of UPI. But does it hold true now? How have the Average Transaction Sizes (ATS) for Mobile Banking and UPI been like over the past seven years?

How do contactless payments using UPI fare, when compared to payments banks' native apps?

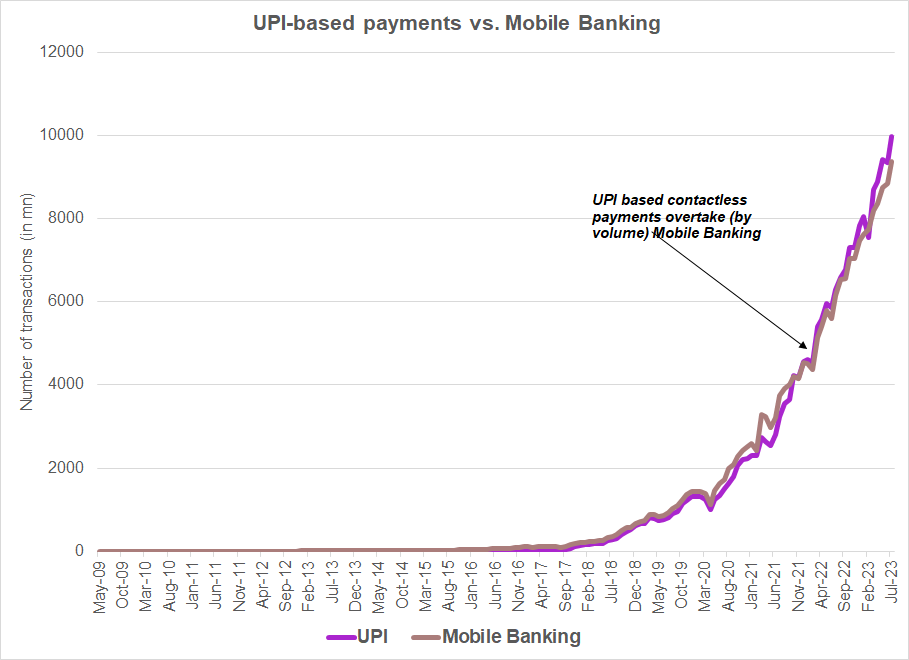

Chart 1: UPI based contactless payments overtook Mobile Banking in October 2021 and have maintained a steady lead since then. Source: NPCI, Reserve Bank of India

The chart above shows how UPI has risen in importance as a mode of contactless payments relative to Mobile Banking.

The number of transactions on UPI overtook those via Mobile Banking in October 2021. They have maintained their lead ever since (Mobile Banking still leads in terms of value of transactions).

As of July 2023, UPI handled 10 billion transactions via different contactless modes - P2P, online merchant payments, Online QR based payments, Offline QR based payments (static and dynamic), feature phone payments via UPI123Pay.

Of these 10 bn transactions, the share of UPI payments via Bank-owned UPI-apps was 1.7% in July this year. This translates to 170 million transactions worth INR 262.5 billion. In fact, since April 2020, from when data for UPI payments are available as broken down by app provider, the share of banks by volume has remained consistently under 3%.

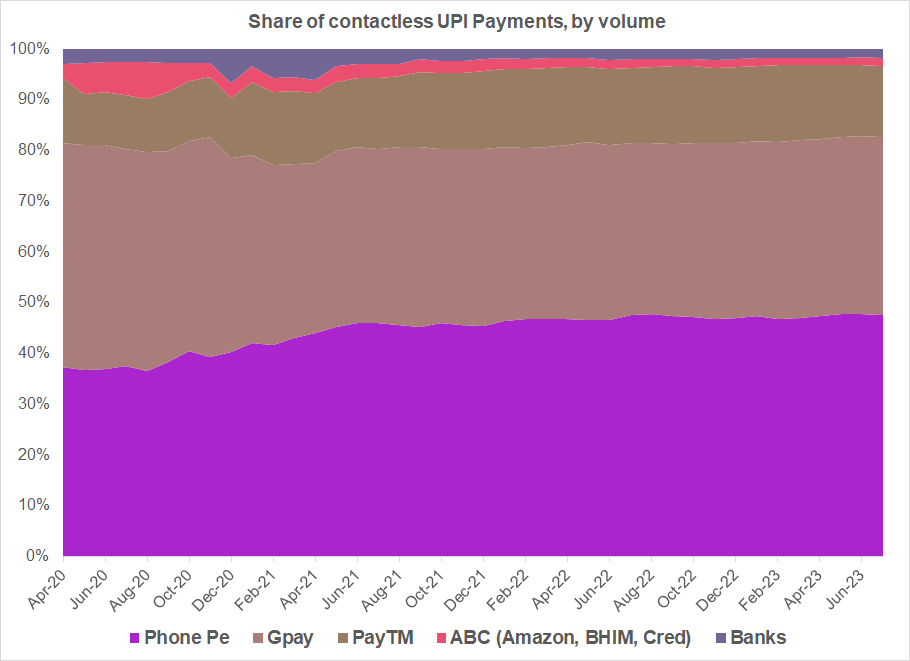

This is despite the fact that UPI-apps from Axis Bank and ICICI Bank have become one of the top 10 apps for payments via UPI since Q4 2022. Their growth in share of payments has come at the expense of BHIM and AmazonPay. Otherwise, the broader trend has been for the contactless payments ecosystem via UPI to consolidate into a three-player market- with PhonePe and GPay being the leaders, and with PayTM maintaining a small, but significant share. The first mover advantage of over 16 years in contactless payments, which banks had enjoyed, appears to not have given them any edge in the UPI-based ecosystem.

Chart 2: PhonePe and GPay have grown their share of UPI Payments. Banks have fought a marginal battle with AmazonPay, CRED and BHIM to take payment market share; Source: NPCI, Author's estimates

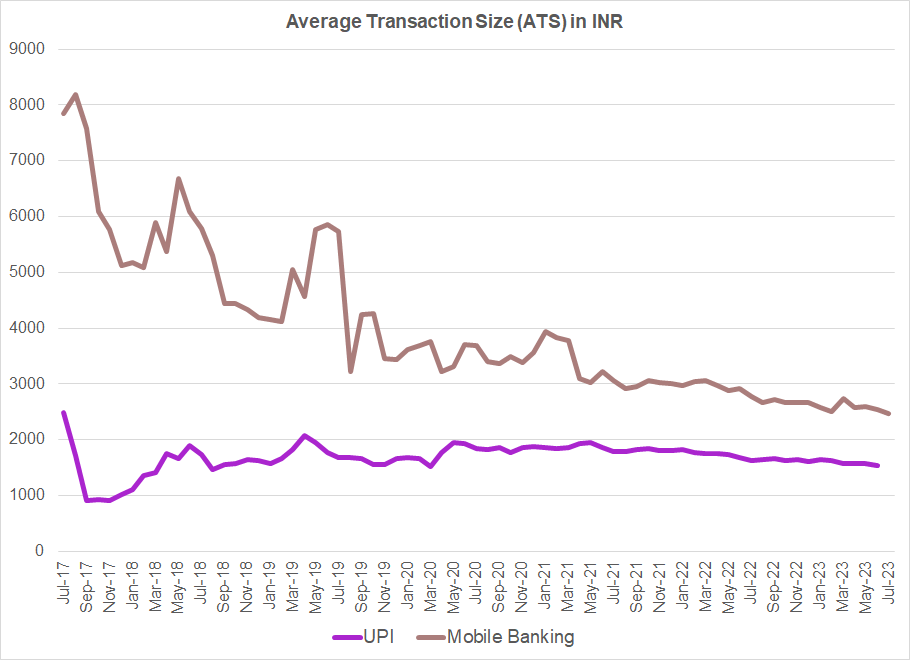

Data from the RBI and NPCI, when viewed together, also show us how the Average Transaction Size (ATS) for Mobile Banking and UPI have evolved. The trend seems to be towards convergence.

In July 2017, for instance, the ATS for Mobile Banking was 7,839 rupees, almost 2.6x the average size of a transaction on the UPI for 3,000 rupees. As the chart below shows, the difference has now shrunk to 1.6x. What could possibly be happening here?

Chart 3: Maybe people are using UPI and Mobile Banking for similar functions now? Source: RBI, NPCI, Author's calculations

One explanation is that we are a digitally well penetrated nation in banking terms at present, but yet have low per capita savings. Ergo, as bank account access rose from 44% of the total adult population in 2011, to 78% in 2021, many of the newly acquired customers were on the lower end of the income pyramid. A good evidence for this hypothesis is the average savings account balance in the country, which has remained stagnant between INR30,000-40,000 over this decade. For the lower middle class which saw this increase in banking access, there isn’t a big case for using Mobile Banking and UPI in differentiated transactions, given the limited savings balances at their disposal. The difference in transaction sizes for making payments usually done via mobile banking (utility bills, rent etc.) and those made via UPI (discretionary purchases, services payments) isn’t likely to be as significant as it would be for higher income cohorts.

The counterpoint though is - “What is the big deal if banks lose out to tech/fintech leaders such as Google and PhonePe in the UPI payments race?”. They aren’t making any money off payments anyways.

I differ. I think the loss of dominance in the payments ecosystem for banks is a strategic weakness that impacts their future valuation (especially for consumer focused banks) in three ways.

Banks risk disintermediation

Over the past year, if you open GPay, which you would, given the app’s 35% share of the UPI payments, you’d see Axis Bank’s ACE credit card being marketed as a way to manage your money and get cashbacks on purchases. On PayTM, similar offers for co-branded credit cards by HDFC and SBI greet you. Nothing wrong with it, they are all operating within legal bounds. But consider the impact they have on a user thinking about a good credit card. You open an app for payment, and you are marketed a specific credit card from a specific company, without being able to see alternatives.

Customer defaults are a powerful thing. As a de facto platform for access to financial services, non-bank UPI apps have become a gateway of discovery to financial products.

Yet they are not obliged to be non-discretionary towards financial service providers. It doesn’t end with credit cards either. It could similarly play out elsewhere. Evidence suggests that embedding an app in payments behavior of a customer might impact urgency driven/ impulse purchases.

PayTM is already seeing this with its lending vertical, where the scale and unit economics of its lending operations has improved in tandem with the increase in its payments market share since early 2021.

As of Q2 2023, as per my estimate, anywhere between 25-30% of Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) loans were disbursed through PayTM. It has a small share of Personal loan distribution as well (1-2%).

Payment apps are like billboards dotting that part of the customer's mind where they make a daily financial decision - of saving, investing and borrowing. Parceling it out to a non-bank, third party payment app is like outsourcing that touchpoint.

There is a direct loss of revenue streams coming from cross-selling and distribution of allied financial products

One of the key highlights of PB FinTech’s IPO back in 2021 was its rapid acquisition of non-life insurance distribution channels from banks, particularly for digital customers.

There aren’t many non-life insurance distributors listed in Indian markets, but conversations with private companies indicate that banks’ share of non-life insurance distribution may already have fallen below 50% (~75% in 2010).

Add to this dynamic the resources that PhonePe (48% of UPI payments) is dedicating to insurance distribution - this could further loosen the banks’ hold in this space. A similar logic applies to fund marketplaces. One doesn’t need to go to one’s bank/ or its app to buy into a New Fund Offering/ start a Systematic Investment Plan. You could simply apply via your UPI payment app.

Banks no longer get to be the gatekeepers to corporate accounts

As of 2023, all three UPI-based payment incumbents -PayTM, PhonePe and GPay - have launched single click bill management services with Gas, Electricity and Local public transport service providers. We don’t get charged when we make a bill payment. But the organizations receiving these payments will be paying a material fee to these third party payment apps for putting the rails in place to receive the bills due. Pre-UPI, banks used to be the gatekeepers managing and receiving these flows.

Today, as long as the basic wireframe for payment receipts by large corporations remains the same, as provided by payment apps - they can easily switch their corporate accounts from one bank to another. There goes the customer stickiness.

Final remarks

In a time when most financial analysts are bullish about Indian banks, this thematic analysis might seem like crying wolf. I do not intend to portray myself as an alarmist here. The analyst view on Indian financials, might be the right perception , in the short run. We aren’t likely to see home/ auto loans being offered on these apps anytime soon.

It might take several years for payment apps to embed themselves completely into purchasing patterns for financial products. But merge ubiquity with convenience, and at least for low risk financial decisions we might see the needle moving away from banks to PhonePe/ GPay/PayTM.

Thereafter, efficiencies of scale that come from cross-selling products, the synergies that come from lower advertisement costs due to better brand recognition and the intermediation that comes as a result of losing out on direct customer connect - all these factors should, in the longer run, end up eating into your valuation.

What should/ could banks do? That is the subject of a more comprehensive analysis, beyond the scope of this essay.