What I read in 2024 - Part 2 of 9

Of Stunted Men and Self Obsessed Polyglots

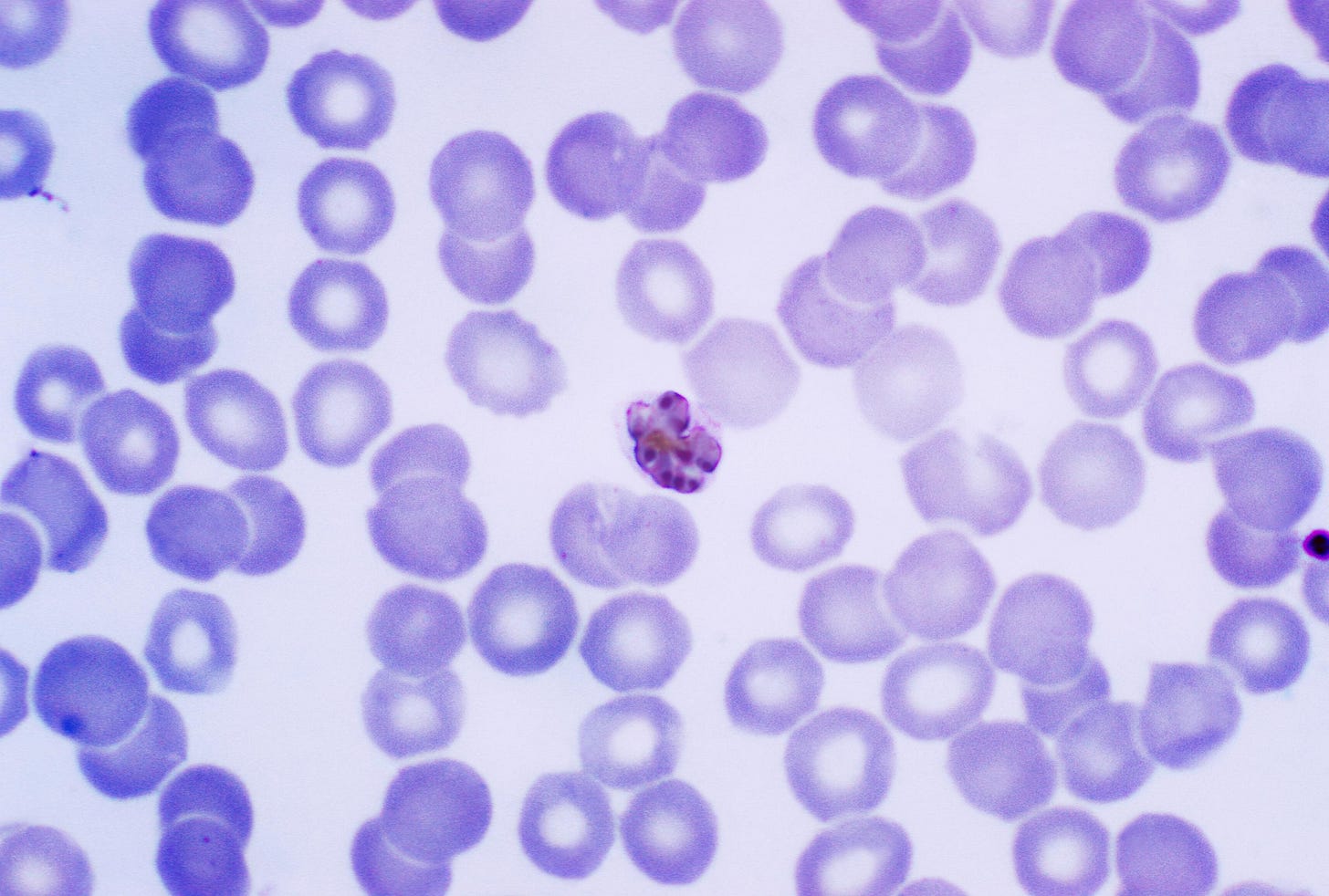

Illustration 1: Mature Plasmodium in human blood, a tell tale sign of chronic Malaria

This is the second part of my reading reviews for 2024 (Read the first part here). Here, I will talk about two less known works by two greats of South Asian English literature that I stumbled upon - a task which I found enjoyable, but hardly memorable.

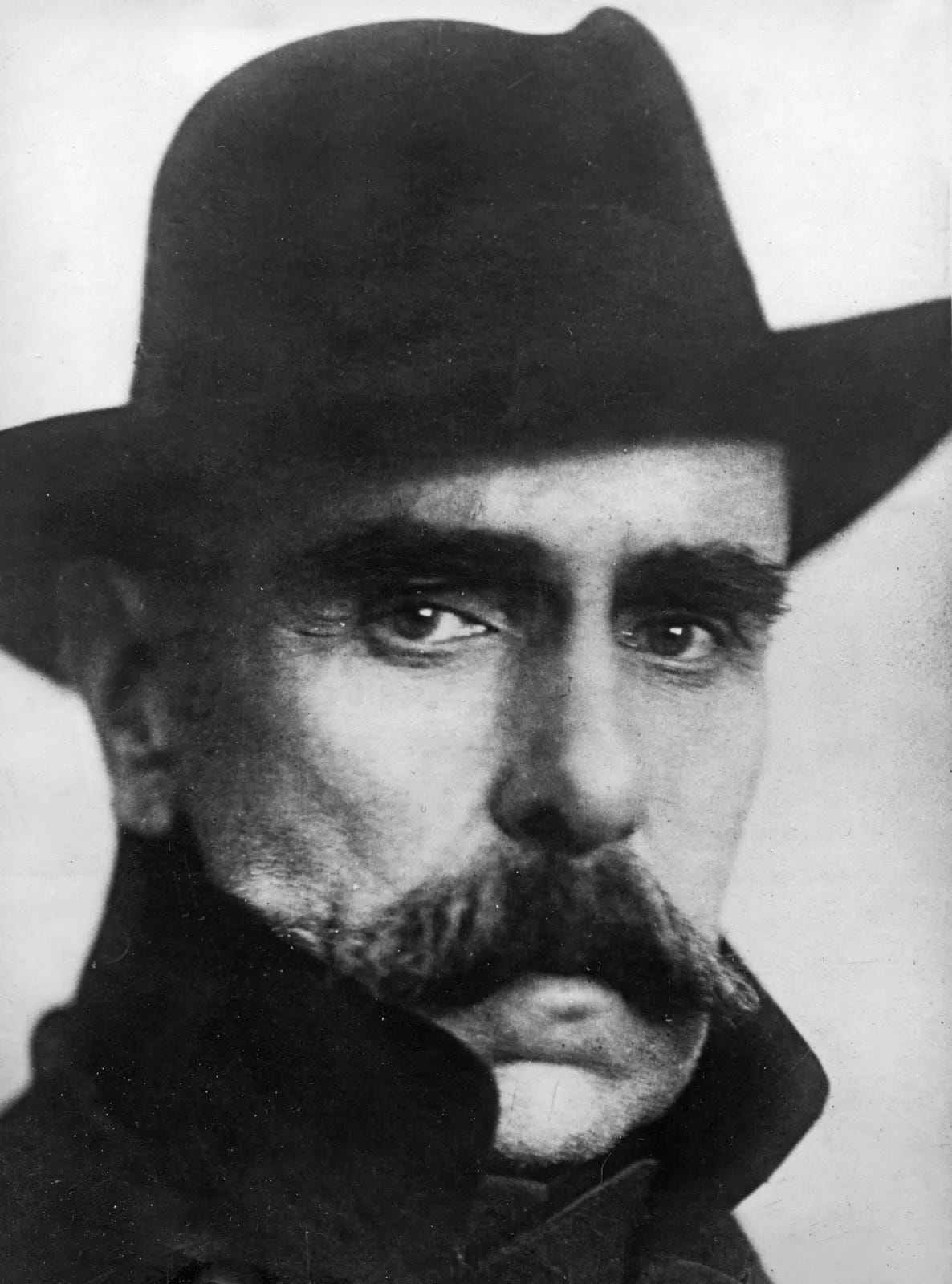

Illustration 2: John Cazale, who plays Fredo Corleone, in Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather Trilogy. Like Fredo, men who never grow up, abound in Narayan’s world, including “The World of Nagaraj”.

The World of Nagaraj is RK Narayan’s penultimate novel. It is set, like others since Swami and Friends, in the fictional town of Malgudi. But if Malgudi is an intricate fresco of life in a 20th century south Indian town, the shades of which you can still find in old Bangalore, the World of Nagaraj is an like an out-of-place, smudged folio in it.

It is a novel whose fall in standards seems starker. The more so because it is set in the same universe (and created by the same author) where gems of English literature like The Guide and Swami and Friends were set. Narayan lets himself down in this novel, possibly because he wrote it while he was in his 80s.

Reading it felt like listening to someone talking about the contemporary world from the backseat of society. Their perceptions being formed by distorted reflections; the gaps in those perceptions being filled by lived experiences of a long-forgotten time. No wonder the entire setting of this novel seems fabricated. Consequently, and the nature of its characters caricatured, approximately in inverse proportion to their age.

The blurb and the first few chapters promise a lot. A middle aged dreamer who never could come to terms with practicality and adulting; semi-employed tradesmen (photographers and pan shop owners) who cultivate paranoias to get by their days; an under-appreciated wife who tries hard to be the sane part of the couple and allows the dreamer to simply exist - all stock ingredients of an RK Narayan-award-winning-recipe.

Narayan shows his genius in capturing the dialogues between the father figures in the novel - Nagaraj and his brother Gopu. He crystallizes the repartees between the greying siblings in a way no one can, and in a way everyone living in a joint Indian family would identify with. These are the liveliest parts of the novel. But the plot looks equally hollow the moment he moves on to the antics of the younger characters - Nagaraj’s nephew Tim and his wife.

The younger characters are deprived of dialogues. And they hew closely to tropes that any “neighborhood uncle” might have about young couples in ‘80s and ‘90s - an utterly hen-pecked husband, a wife who is not obedient enough, someone so addicted to alcohol that they can’t stop running away to the nearest watering hole. Reading this one was like eating a half-roasted roti.

The challenge with this novel, and the later works of Narayan (in his 80s) is that they never really take off. This one begins with two subplots crammed in an 180-page script. The first is Nagaraj’s obsession with writing the biography of Narada - the celestial sage. The other is his desire to fill the void of fatherhood in his life by parenting his nephew - in a way that only men from his time and place can. You’d expect these plots to intersect somewhere - a comedy of errors that resolves both his instincts of a creator and a parent; or that classic bittersweet realization of the futility of one's fancies that one sees in so many Narayan novels. The readers are thoroughly disappointed, as neither happens. It appears that Narayan lost his taste for this narrative somewhere along the way. And decided to hurriedly close it.

And yet, this book left me with some worthy reflections. On the younger siblings in a joint family system in India, who are perpetually condemned to extended adolescence by the accident of birth. Nagaraj’s naivete and impracticality springs from the fact that even in his 50s, he is still the younger brother. He is expected not to make big decisions in life (which are reserved for his older brother). He is never taught to either stand up or fend for himself.

This book was a throwback to all man-child characters - uncles, great-uncles and aunts- who inhabit the Great Indian Family. The worst of them depressed; the best of them trying to maintain a sense of cheerful normalcy by indulging in quixotic pursuits like writing biographies of non-existent mythological characters. There is a room to explore this space more - to explore the inner lives of these stunted men, these eternal, coerced, betas of the joint Indian families. There’s a novel here.

Read this one if you are a die-hard Narayan fan. It does add to your knowledge if you wish to understand his repertoire as a whole. There are a few pearls of wisdom here and there; a few chinks through which his observational genius shines. But taken alone, this is a pass. You aren’t missing much.

Illustration 3: Julius Wagner Jauregg, the first psychiatrist to win the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1927 (from where else but Austria), who experiment with the use of Malaria to cure dementia- a course of treatment that forms the core narrative of The Calcutta Chromosome.

The Calcutta Chromosome is the first, and only, novel of Amitav Ghosh that I have read so far. I bought this back during my college days when they used to still have “book fairs” twice a year on campus. Ghosh, who had recently written The Hungry Tide and The Sea of Poppies, sounded so cool then. A brag about having read his earlier works before he became famous (like this one) seemed to be worth it. More than 15 years later, when I read it, it felt like a nice read, but far from the promise that its cover and the chosen topic had held for me when I had purchased this book. Those who have read more of him tell me that he is a polyglot, someone who researches the subjects and backdrop of novels with encyclopedic obsession and in meticulous detail. That's something that Dan Brown can barely aspire for. But this is one occasion where juggling a thriller alongside a history of tropical medicine in the 19th century sacrifices the suspense of the former, for a dramatization of the latter.

This is a book that should have been fatter. Especially because in a rush to finish it, Ghosh smears a broad palette of colors across a bunch of characters central to the plot. Making them look like stereotypes.

Like the TV version of Game of Thrones, the author places riveting multiple narratives across time and geography of Calcutta in the first two thirds of the book, but he simply doesn’t know how to tie them all. As if someone gave him a missive to finish the novel quickly, the entire chessboard set up by him collapses in a few moves. Overpromise and Under Delivery.

On the fun-read side, there’s this story of a Railway employee turned author having been dropped off at a ghost station with a ghost train running by it. An episode that makes you feel the terror of being run down by an evil Lovecraftian force which doesn’t like to explain its reasons. But then, after 2 minutes, you ask - “why was it relevant to the entire story?”. Like Arya Stark and White Walkers in the Game of Thrones, this is also one of those dead ends you disastrously crash into, in the hope of figuring things out.

Furthermore, obviously having been written for a predominantly non Indian audience interested in India, it liberally uses the familiar, belabored, hand-wavy magic trick of leaning on oriental spiritual cults as the underlying explanation for the disappearances, murders and attempted murders in the book.

The ultimate feeling I got reading this one was like seeing a YouTube clickbait - before “YouTube” and “clickbait” were even words. The history of malaria research in India, the unsung native heroes who worked with Ronald Ross and the audacious attempt to cure syphilis using malaria that even won its pioneers a Nobel Prize in Medicine - these real life historical events are rich with the possibilities of a fantastic sci-fi-thriller. Ghosh never compromises on the details and authenticity of facts here. But like someone watching that clickbait video 10 seconds longer for the magic reveal, the reader here is dragged through an interesting premise into nowhere. In the end, you try to rationalize the experience. You pretend to have not understood it fully. You tell yourself that you will read this again. There is a funny feeling of being auto-gaslighted, where you want to find a deeper meaning in a plot “flattering to deceive”.

That said, it is important to be charitable to Mr. Ghosh. Maybe this is one of his lesser works - a vanity project when he was still trying to find the magic proportion to mix a narrative and its historical/scientific background. Perhaps his later works became much tighter. I don’t know yet. I haven’t bought another book of his. And though this one was enjoyable, I am not going back to it anytime soon.

In the next part of this essay, I will be talking about two books on history. One a controversial take on a figure whose reputation needs a revision. The other, the subjection to history of our immediate past, and a meditation on how and what we remember.

Check out the Hungry Tide, and Sea of Poppies trilogy. Amitava Ghosh definitely will fulfill your desire of a much fatter book. They are so descriptive. Just , like literally today, finished his “In an Antique Land” on an Indian slave, Jewish merchant and Amitava himself in Egypt. Fascinating book but yeah not as descriptive as his other works.