When Dollar Falls (Part 1 of 5)

What elevates a currency to a Global Reserve status, what makes institutions stick to it and what signs indicate a change in Global Reserve currency status

Figure 1: A Hunnic coin from between 490-515 CE, in Gupta style; Source: https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=301345

Prologue:

528 CE (India): It has been almost two decades since the Gupta Empire, which ruled large parts of the northern Indian subcontinent and the Deccan (indirectly) for the past 180 years suffered a debilitating blow at the hands of Huns. The Guptas, as they exist, are but a small kingdom in the far eastern Gangetic Plains, their remaining strength sapped by their own generals who have benefitted from the anarchy following the invasion of Huns, and have rebelled to set up small fiefdoms. This year, one of these principalities, the Aulikaras, under its chieftain Yashodharman, would lead a confederacy to finally vanquish the Huns in a battle in Malwa (Western Madhya Pradesh), and permanently extinguish their power in Northern India and Punjab over the coming decade. The trade routes of Malwa, which connect Northern Indian plains to Gujarat sea coast and thence to lucrative markets of Persia and Byzantium, will fall in Yashodharman’s hands, laying the foundation of a short-lived Aulikara Empire.

And yet, the coins used by Huns and later the Aulikaras, continue to be struck in the Gupta style, using the Brahmi script patronized by the Guptas. Weights, measures and coinage - the essential standards of trade in the globalized Late Classical India will continue to follow Gupta patterns for another four decades, almost 50 years after the House of Chandragupta Vikramaditya ceased to exist. Even in its absence, the memory of Guptas was potent enough to be appropriated by their successor states in their currencies. After all, as rulers, Toramana, Mihirakula, Yashodharman - the warlord kings of the 6th century CE, couldn’t hold a candle to the justice, prosperity and unity ushered in by the Gupta Golden Age (350 CE- 460 CE).

Currencies are more than just a token of power struck by a victorious military power. They are an interplay of mutually agreed norms of exchange guaranteed by a state/ issuing authority which creates and upholds a consistent rule of law.

How to know when a currency is in a relative decline when it comes to its Reserve status?

The relative decline of the United States in the 21st century, the rise of a multipolar world in which all multilateral international organizations are not dominated by the G7 and an unprecedented polarization in US politics, has once again reignited the chatter around whether we are once again at the cusp of history - when Dollar falls from its pedestal as the Global reserve currency and is replaced by someone else (Renminbi? Euro? A confab of cryptocurrencies? Indian Rupee? Russian Rouble?). In their typical nature as content platforms, Google, Youtube, Facebook and LinkedIn are full of articles, videos and news with polarizing headlines, full of a sense of urgency - exhorting one to click on them, get a bit agitated after reading them and then sharing it with their friends and family for cognitive brownie points.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Money, or currency, is something we use tens of times a day; it is something that works for us when we are asleep (if we have invested well). Therefore, even the most complicated aspects of what makes one form of money desirable over the other, are perhaps easier to explain given its intersection with our daily lives, unlike maybe geology or veterinary sciences.

In this series of essays, I will try to explain what elevates a currency to a Global Reserve status, what makes institutions (central banks, payment systems, people and corporates) stick to it and what signs indicate a change in Global Reserve currency status.

In 1991, before he became a policy warrior, Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman laid out a simple framework to help us understand the key functions a currency must fulfill, in order to attain a Global Reserve status. The users of a currency, outside its borders, can be classified into two sets - Central Banks and Private Sector (which includes corporates as well as individuals).

Why do Central Banks hold foreign currency assets?

Almost all Central Banks across the world hold some of their assets in currencies of other countries. This doesn’t mean that your Central Bank - whether it is the Reserve Bank of India or the Reserve Bank of Australia, necessarily holds a deposit account denominated in Dollars or Yen or Sterlings. They could also hold short-term securities issued (in most cases) by the governments of those countries - 3-month US Treasury bills, 3-month UK Treasury bills and so on. About a hundred years ago, when it was the norm for the Central Banks to be privately owned (Swiss National Bank and the Bank of Japan still are), they used to hold foreign currency assets, mainly to earn an income to offset deposit rates they had to pay to banks and other financial institutions. In the modern times, when most of the banks are either wholly owned by the government or are statutory bodies set up by an act of the government, the purpose of earning income on a foreign asset becomes secondary. Today, the most important function of any Central Bank in the world is to act as the Dealer of the Last Resort, for all the entities transacting within its currency jurisdiction.

Figure 2: Bulk of the Global Central Bank Reserves continue to be held in USD

As the holder of FX reserves, a key motivation for a Central Bank is to convince those who use its own currency that there will not be an abrupt dislocation in the value of their foreign currency obligations, as denominated in the Central Bank’s currency. In that sense, FX reserves are used as a tool to determine the floor and ceiling of a range in which Central Banks allow their currency to fluctuate. Furthermore, as the travails of both Pakistan and Sri Lanka have shown us in recent times, insufficient FX reserves can quickly act as a drain on economic activity, in case they end up not being able to cover state debt and import obligations.

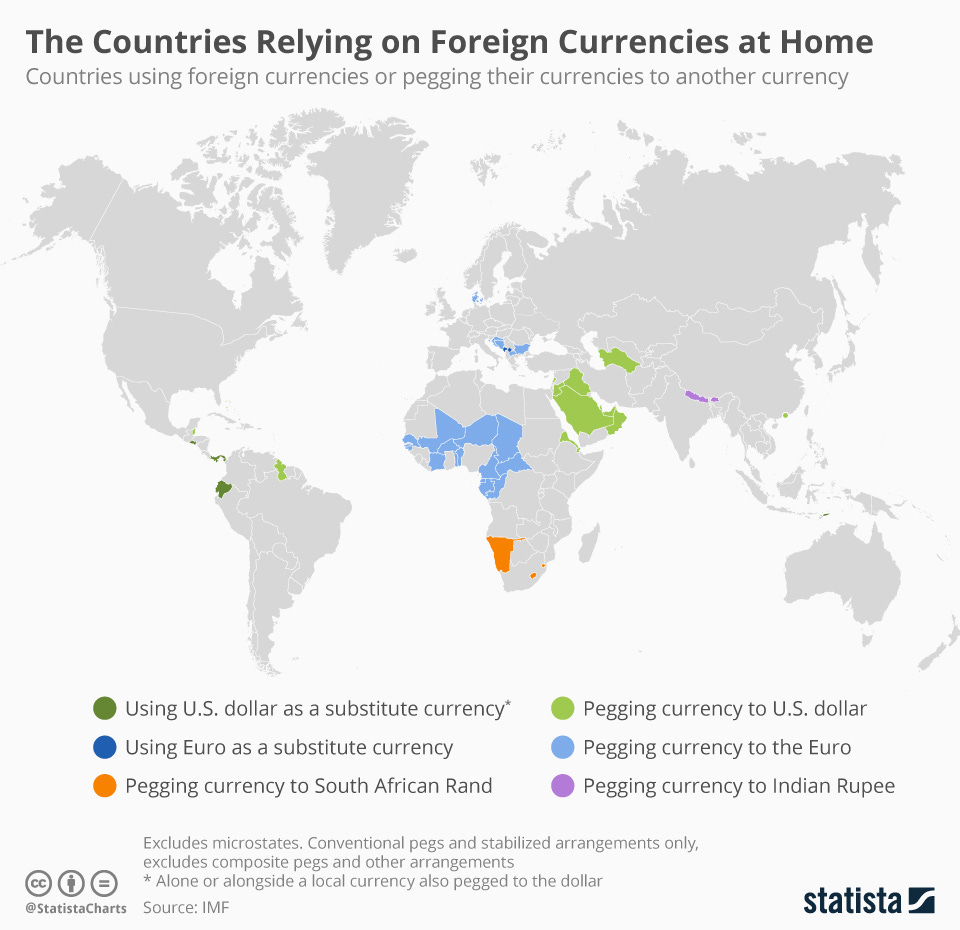

Figure 3: Trade usually determines a country’s decision to peg its currency to a foreign currency

As an edge case, Central Banks of some countries (UAE, Saudi Arabia, Panama, Burkina Faso et al) also hold substantial amounts of FX Reserves simply because they have decided to directly or indirectly fix the value of their domestic currency (peg) against the USD. It works wonderfully if you are an exporter of a single commodity (like crude oil) and depend upon imports of everything else to sustain yourself as a nation. For instance, Singapore, which exports services to the world but imports almost all its primary and manufactured goods, keeps a significant amount of its Central Bank assets as a portfolio of currencies, likely weighted by the share of its imports denominated in that currency.

If these are the reasons why any Central Bank would hold foreign currency reserves, what determines their choice?

Credibility of the foreign central bank and the government

First, the monetary and exchange rate policy settings of the country issuing the foreign exchange. Think of yourself as the Governor of a Central Bank. If you were to buy Dollar, Euro or Sterling assets, what would drive your choice? Since these are predominantly bonds - you would worry about the credit risk. And I am using the credit risk here in the broadest possible manner. As in, to what extent the issuer would ensure that the value of the asset (government bond) purchased by you remains reasonably intact and, importantly, redeemable. A good candidate would be a currency asset whose supply doesn’t fluctuate erratically, ensuring that its value remains stable. You’d want both the central bank and the government of the country whose currency you hold, to have predictable monetary and fiscal policies - where there is a defined target for the issuance of debt and money supply and where there is a transparent disclosure of any deviance from that path. Furthermore, you would also want the central bank issuing the foreign currency to be always ready, either directly or through other banks, to exchange your foreign currency assets in any other form you want. It cannot abruptly freeze its capital market for foreign investors, including you as a central bank.

Liquidity and depth of the foreign currency market

Second, one can argue that when it comes to monetary and fiscal policy control, a country like Switzerland is much more disciplined than Europe and the US. Then why don’t central banks hold more of Swiss Franc in reserves? The reason is liquidity. Even if Switzerland is one of your largest trade partners and even if you have borrowed significantly in Swiss Francs, you may still not want to hold much of it. The simplest definition of liquidity is the ability for any transacting party in finance to execute a trade with the least delay, at the least transaction cost and with the least impact to the price of the asset that they are selling. For a currency to be liquid in the international markets, you would require - many people wanting to transact in it, a variety of issuers issuing securities in that currency and a number of risk management instruments (options, futures, forwards, swaps) that help protect the transacting parties against any adverse movement in prices. All these three elements require not just governments and central banks of the issuing countries to be fiscally disciplined. They need two other things. One, a deep financial market where the financial sector is well developed to offer a variety of financial instruments of varying degrees of risk and return. Two, strong corporate governance and market regulation laws that ensure that even the non-government entities dealing in these securities, as issuers or brokers, are prevented credibly from committing excesses.

Determination of the Global Reserve issuer to defend their status

Third, and this is one of the more underappreciated aspects of why Central Banks would choose a particular foreign currency asset over another. However, in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 Panic, it might be the most important thing that kept the US Dollar maintain its hegemony. This is - the determination of a foreign central bank to do what it takes to preserve its Global Reserve status.

A Global Reserve status does not come without its costs. Yes, it creates a natural market for the government of that country to issue debt enabling it to award trillions in stimulus packages without affecting its sovereign credit status significantly. And it gives its domestic banks an unfair advantage in the foreign markets as they become dealers of a highly desired currency. But on the other hand, it also squeezes on the export sector of the country precisely at the time when an economic downturn happens, as the country issuing Global Reserves sees a massive increase in the demand for its home currency, leading to a currency appreciation and a loss in cost competitiveness. Second, as for the USD, a larger market in your own currency can start developing outside your borders - as the Eurodollar market did in the run-up to the Global Financial Crisis. The central bank issuing the currency has little oversight of the problems brewing outside its borders- the banks and financial institutions issuing Eurodollar assets in Europe, UK and international markets in the early aughts were not under the supervision of the Fed and many dangerous cross-asset linkages, which led to the collapse of asset prices across the globe - leading to a recession even in the US, could not have been foreseen.

Even so, if the issuer of the currency believes that the benefits of this title outweigh its costs, it is likely to be preferred by other Central Banks. A good example of this action would be the Fed’s aggressive use of Central Bank Swap lines in 2008 and 2020. As we have discussed earlier, one of the key functions any Central Bank keeps FX reserves is to be the Dealer of Last Resort in its own currency market. In 2008 and 2020, Central Banks in countries such as Australia, Brazil, Mexico and Singapore saw holders of assets in their domestic currency rush to dump them and demand dollars. What the Fed did here was to provide them access to dollars, at a fixed exchange rate, for a limited or unlimited period of time.

Let us explain it through an illustration. For example, the Fed could enter into an agreement with the Bank of Japan to swap USD 1 trillion on 1st October 2008 against JPY 100 trillion (assuming an exchange rate of 1USD = 100 Yen) for a year. On 30th of September 2009, it would swap back JPY 100 trillion for USD 1 trillion, even if the USD/JPY exchange rate would be 1 USD = 115 Yen on that date. This ensures that as a central bank, the Bank of Japan would be bearing no exchange rate risk and would have an assured supply of USD for any entity who would want to exchange JPY for USD. In essence, this action would help tamp down the run on JPY and make the USD the preferred choice for the Bank of Japan when it comes to keeping foreign currency reserves.

The Fed’s determination to do what it takes, even at the cost of flooding the global markets with its own currency and further reducing its oversight of how and where its dollar assets are used, has played a big role in helping it retain its position as the Global Reserve currency. Indeed, in an article, Economist and historian Adam Tooze credits the Central Bank swap line agreement by the Fed as helping restore the confidence in those countries’ central banks which benefited from this policy, and this in turn helped some emerging market central banks to increase their holdings of Yen, Australian Dollar and the Euro.

In the next part of this essay, we would examine the same question - what makes a particular currency a preferred global reserve, from the point of view of the private sector.