Is there a template to successful digitization in India? - Part 1

A tentative hypothesis of how “digital diffusion” works

This note is a tentative hypothesis. It is also my first attempt to, put out in the open, a theory that I have begun to develop, as a side-project during the course of my daily work within investment banking. There, I look at companies in the internet/digital space. I see it as a stroke of good luck that allows me to devote my most productive hours of the week listening to different companies, founders and technologists and poring over large pools of data to make some sense of where the industry is heading.

It is a collection of circumstantial evidences, which to the best of my knowledge are original. While it does explain some common features and subtle nuances in what I term as “digital diffusion”, it needs to be backed up by further research. This is where I would need your help. On request, I will be opening up all the data backing up this analysis to interested people. No one would be happier if this helps me to jam with some of you to dive deeper in exploring these questions.

Prologue

A little less than five years ago, when I was looking to recruit out of business school, there was this obligatory question that we needed to prepare for. “Tell us about a successful case study of digitization in India”. Pre Covid, when I graduated, the reflexive answer used to be - UPI-based payments.

Since then, I have tried to understand why that was so with the UPI.

There are excellent explainers for UPI from a “payments perspective”. That is, most of their whys focus on - ease of use, accessibility of its software interface and innovation in payments systems. But here is the problem. The takeaways from these explanations are great if one wants to design a great payments system.

If I want to revert to the broader question posed earlier - digitization of economic transactions - there seems to have been precious little one can find for policymakers/entrepreneurs looking to digitize other aspects of our economy and reduce transaction costs.

If you look around, It isn’t just payments that have moved online in India in the past 7-8 years. The customer default for brokerage accounts and toll payments has become digital too.

So, is there something common at work which has made it easier to make payments, sell/purchase shares and pay road tolls online? And how is it different from other economic transactions such as collating and transferring one’s health records digitally (Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission - ABDM), setting up a digital storefront (Open Network for Digital Commerce- ONDC) or creating a movable digital repository of all the indicators of one’s credit eligibility (Open Credit Enablement Network- OCEN) - all of which haven’t/ are yet to take off as spectacularly as the former three?

A broad roadmap to my quest- to which you are invited with your contributions

Over the past six months, I have tried to tease out some common developmental trends in the aforementioned successful cases of digital diffusion, which when book-marked against policy actions and product innovations, seem to suggest that there is a template. That forms the first part of this note.

Since digital diffusion implies a democratization of digital access to some process or transaction, what happens to average transaction sizes (ATS) when economic transactions digitize further? It is an important question for businesses building in this space. As the accessibility and adoption of your services improves, what happens to your marginal revenue per user? I look at the evidence from these three successful use cases to tease out some answers to this question.

And finally, I explore a question worth answering for investors allocating to this space - what kind of market structures emerge in a sector where transactions move from offline to online in a short period of time? Does it become a winner take all for digital-first firms? Do we have stable, but significantly large shares of the pie taken by legacy firms and digital-first firms?

Notice a similar shape?

If you are in India, you might have an instinctive understanding of what I mean when I say that payments, toll collection and broking are the most digitally diffused economic transactions in the country. Everyone uses them, don’t they? That said, it might serve a good purpose to see how similar these three processes, in terms of growth in transaction volumes, have been over the past 6-7 years.

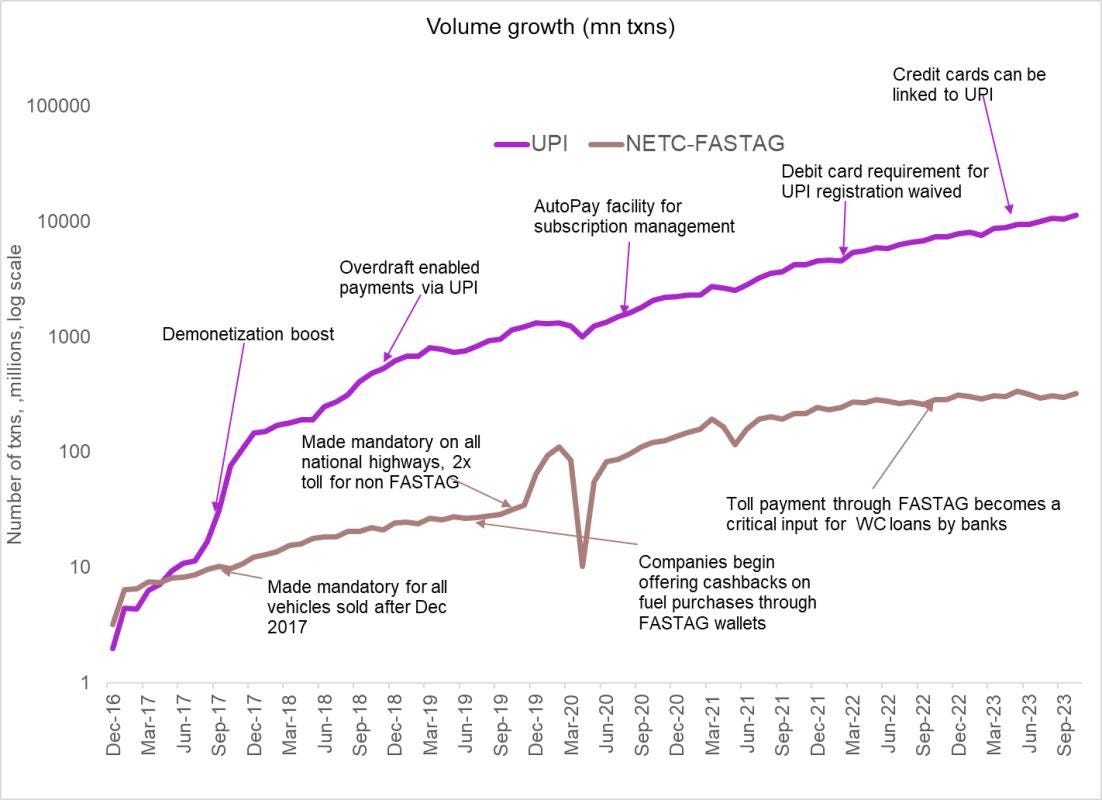

Figure 1: Transaction volumes have followed a typical exponential curve in successful cases of digital diffusion; Source: NPCI

The picture above shows how transaction volumes for UPI and NETC-FASTAG (the RFID enabled electronic toll collection system) have performed since their launch in 2016. The graph is book-marked with what I believe are policy actions and product innovations that created important inflection points in their growth journey.

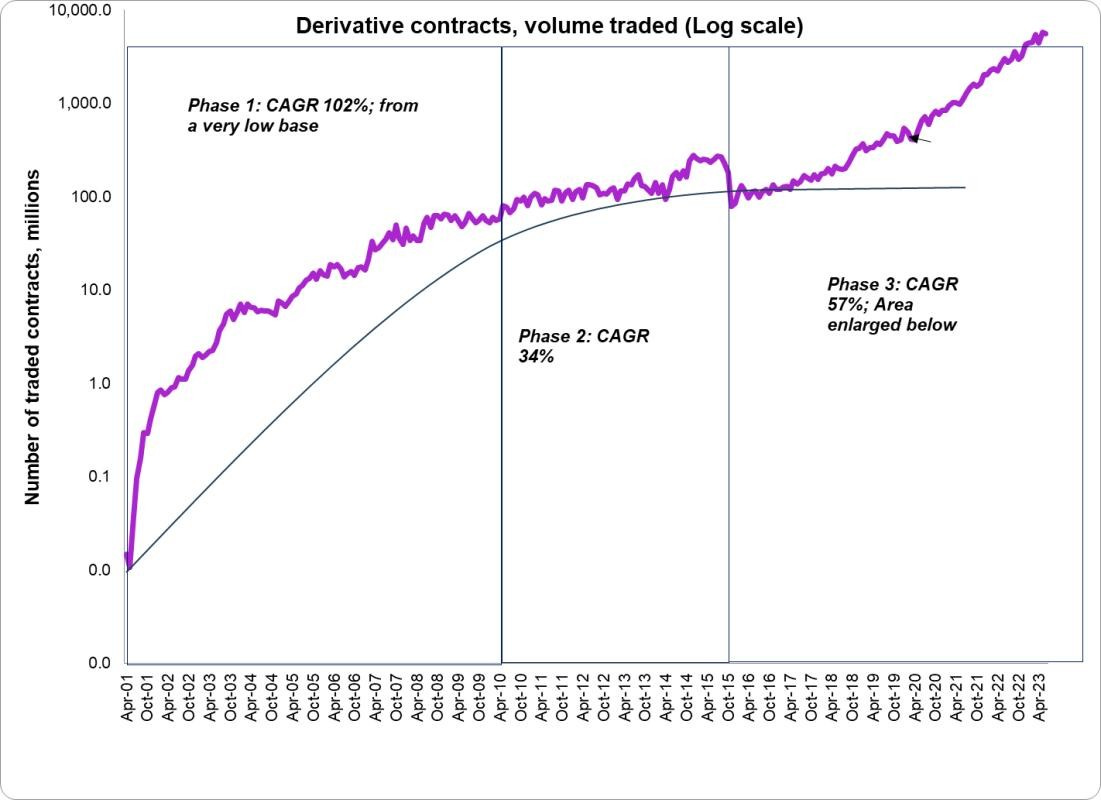

Retail trading via brokers is a bit different. Spanning over the past two decades, it has had two inflection moments. The first one in the early 2000s was led by a deepening of institutional participation in equity markets and the latter, since 2015-16, being driven equally by institutional and retail investors.

The chart below uses Futures and Options (F&O) trading volume as a proxy for the growth in broking (F&O volumes dwarf equity trades by a factor of ~120x).

Figure 2: F&O trading gets a second wind in 2015-16, after its initial growth from a low base in early 2000s; Source: SEBI, Author’s calculations

Figure 3: The hockey stick growth since 2015-16 is different, as it is enabled by a 7x increase in the number of retail broking accounts, which seem to have grown steadily even through the recent market turbulence in 2022.

These familiar shapes also carry something common among enablers for such growth. I believe that is down to three factors, the combination of which is missing for other digitization initiatives in India in one or the other way.

The Importance of Institutional Design

First, all the successful initiatives were nurtured and are actively led by State-adjacent, but independently run and managed entities. For payments (UPI) and electronic toll collection (NETC-FASTAG) this body was the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). For brokerage, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).

Creating a positively stated statement of purpose helped as well. NPCI was created to “provide infrastructure” and “bring innovations in payment systems”. This is unlike the state-adjacent organizations of 20th century India, whose preamble provided a greater heft to protective, regulatory and supervisory functions.

One can argue that SEBI still maintains some of that paternalistic flavor in its statement of purpose. However, it has been far more proactive compared to its regulator peers set up in the first 50 years of independence, in bringing initiatives that are pro-innovation - mandatory digital KYC (2020), encouraging fractionalization and retail participation in equity ( since late 1990s), commodities (2015) and corporate bond markets (2022-23).

Also, The career trajectories of senior executives of both these State-adjacent institutions (NPCI and SEBI), especially in the high growth phase of digitization since 2017, show a significant amount of time spent in the private sector.

It seems that, to the extent that the fulfillment of government’s policy goals in digitization is concerned, banking on leaders who are not traditionally drawn from bureaucratic ranks works better.

Furthermore, staying at an arm’s length from the government helps. This is especially so in India where cycles and epicycles of state and national elections determine the pace, bias and urgency with which policy goals are advanced in fully state-owned and run organizations (e.g. Indian Railways). On the other hand, being close to the State also creates a perception of being above the fray and having the ear of policymakers.

The criticality of getting the policy nudges right

Exogenous policy shocks, intended to kickstart the digitization of an economy, are the ignition to digitization. Pure free market models of the economy would suggest that simply having a superior technological alternative to a process - digital KYC instead of paper based KYC for instance- would be sufficient in gradually letting better solutions diffuse through the economy via rational choices being made by the users. Practically, that doesn’t happen.

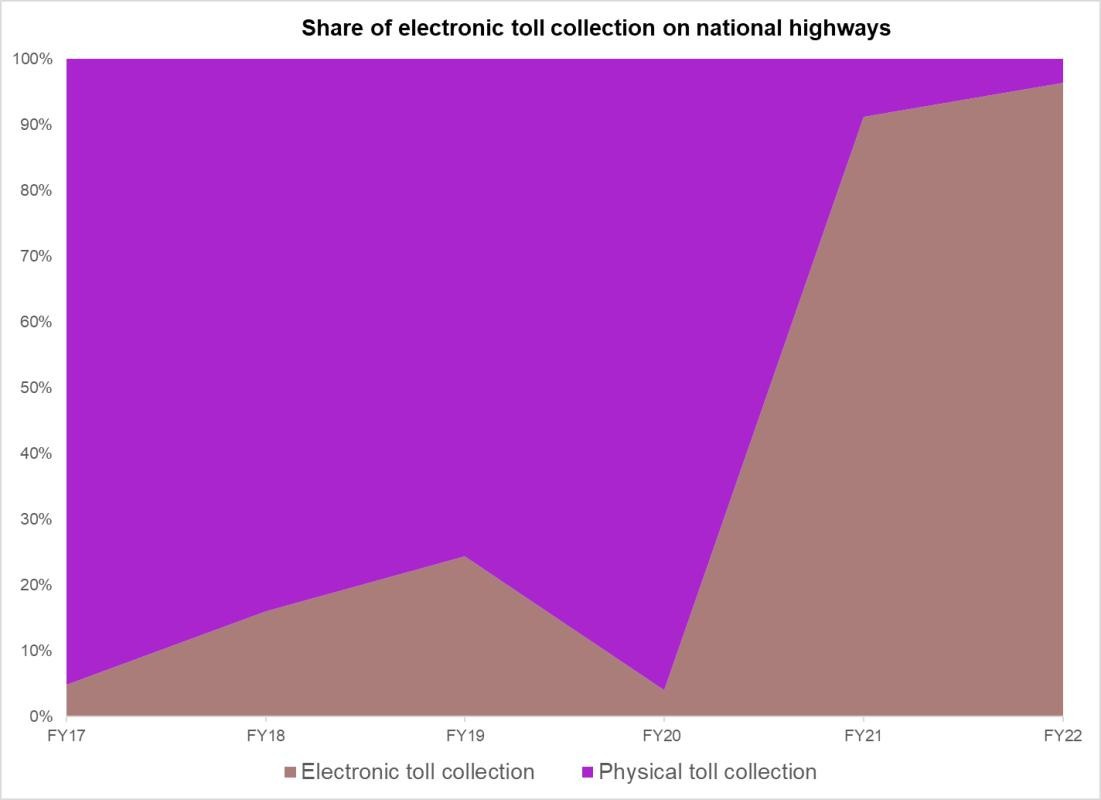

A good case in point is NETC-FASTAG. Launched in 2016, the program was promoted by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MORTH) by announcing dedicated lanes for vehicles who adopted electronic toll payments. It was certainly a better service for someone paying toll -the halt time for NETC-FASTAG enabled vehicles was < 3 mins at a toll gate compared to > 5 mins for a vehicle that paid in cash . Between 2016-19,despite transaction failure rates falling rapidly for payments through the next two years, the share of digital toll payments to total toll payments on national highways remained under 25 percent.

It was only in Q4 2019, when the government made electronic toll payments mandatory on all national highways and a penalty of 2x toll for individuals not using was imposed that the digital adoption of toll payments saw a spike. Within 18 months of this order, over 92% of all toll collections on national highways went digital.

Figure 4: A policy directive acted as an exogenous shock, pushing up the share of electronic toll collected on national highways to over 97% in FY22; Source: MORTH

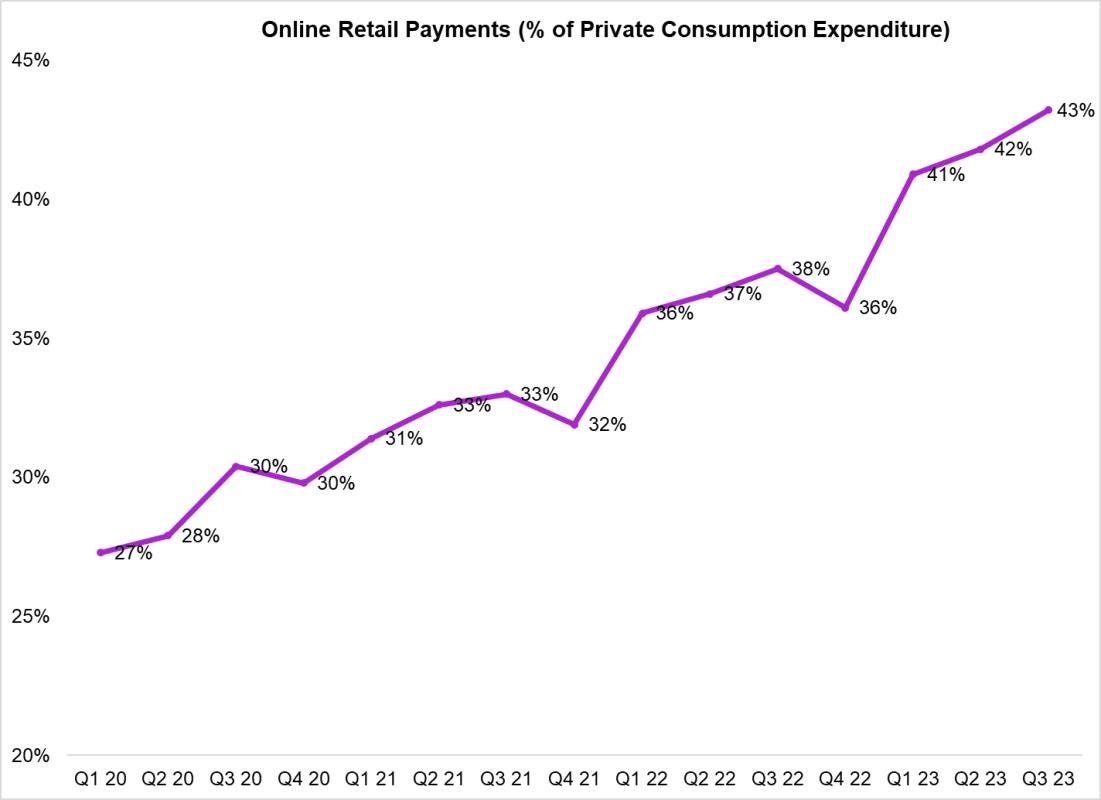

With UPI, the jerk to the status quo came from demonetization. Initially positioned as a move to fight against counterfeiting and money laundering for terrorist activities, against which it has had limited to no success, demonetization in 2016 definitely had an impact on formalization of the economy by moving a significant share of payments online. I estimate that over 43% of the country’s consumption expenditure now happens through online digital payments. This still underestimates UPI’s prevalence in payments given that a lot of peer-to-peer money transfers are not counted as economic activity.

Figure 5: Demonetization, followed by COVID lockdowns four years later, created an economy where close to half the payments for private consumption (by value) happen online. Data on Payment system indicators by RBI are available only from 2020 onwards Source: RBI, NPCI

For brokerages, a move in 2020 provided a mighty kick to digitization in brokerage, forcing both the current players and incumbents to move away from pen and paper processes. Via circulars in April-May 2020, SEBI made it mandatory for all new customers being offered any financial product to have a CKYC registration. This required all brokers to digitize their customer onboarding interfaces and create a central repository of identifiable KYC data. Digital first brokers, who anyways had the processes in place for this, raced ahead.

Digital pioneers with a mature tech-stack but a nascent market reach

Finally, digital-first players in each of these segments were small enough within the broader market in which they were competing. This created an incentive for them to adapt their tech to the blueprint being suggested by the government and enrich their offerings to keep the first time digital users within their ecosystem.

Let us go back to 2016. PhonePe, founded less than a year ago, was an instant mobile payments enabler app recently acquired by Flipkart. It had built the rails for making instant online payments to ecommerce but was still a niche play - its users coming to it only for shopping online. Along comes UPI in mid 2016 and it opened a breach for PhonePe (and later GooglePay and PayTM) to partner with banks to provide instant payment services for use cases other than captive online shopping.

In an earlier post, I have written about how UPI overtook mobile banking, as third party payment apps like PhonePe and GPay started to compete with banks on owning the payment touchpoints. These companies, without UPI, despite having the tech to enable instant payments, wouldn’t have been able to so comprehensively penetrate the payment behavior of Indians.

Since then, the leaders in payments space - PhonePe, GPay and PayTM- have worked to introduce more features - travel booking, investing, insurance, bill payments- to ensure that those who entered their walled gardens lacked for nothing when it came to their daily payment transaction requirements. Form and features have followed market incentives.

In 2019, a similar story unfolded in electronic toll payments. PayTM had received a payments bank license in 2017, but was a microscopic player at the time in merchant payments. Even in retail payments, there were many places where people still made cash payments - meaning that the consumer intelligence, with which fintech players in payments hoped to build their lending engines, was simply missing.

There was simply no way in which payments behavior in ecommerce and retail transactions, which was picking up, could spill over to toll collections. You want online bill payments because you are already buying goods online, so why not service subscriptions. You want online insurance because you are already booking travel tickets online, so why not ensure your trip too. But there is no “and” to toll payments. There is no frequent daily consumption activity that goes alongside it. Left alone, payment banks and fintech players were neither gathering consumers nor were able to cross-sell their services on toll payments.

That is where the fillip from the government’s directive on electronic toll payments came in Q4 2019. Once that external shock therapy came into play, it also created a pressure on the other side - for fintech providers to leverage on this opportunity. Airtel, PayTM and Logistics tech firms (Blackbuck, Park+ etc.) became the front runners in issuing RFID enabled FASTAG stickers to drivers and used the intelligence to provide them with tailored fuel plans, card products (PayTM) and even working capital lending with their partner banks. The story of the latter - Logistics fintech companies- is something I will touch upon even later in this essay. At this point, it is sufficient to say that their success shows how even non-fintech digital players can aid digitization by tapping into their customer base and developing adjacencies for future growth.

In digital broking, the prevailing incumbents - Zerodha and Groww - predate the retail trading boom that started in the 2020s.

Zerodha was already a market leader, in terms of retail trading accounts, in 2018 (I will talk about this aspect later as well). Its innovations were groundbreaking - paperless onboarding, regular investor education in-app, commission lite trading- but still depended on word of mouth, long CAC cycles to deepen its customer base and engagement. It could have remained the top broker by trading accounts for another few years. But with ~USD 75 million in revenues, it had less than 1% of its share in value terms.

Regulations in 2020, which required all brokers to digitize new customer KYC records, provided the incentive for digital first brokers to induce larger and more active clients to switch accounts in their favor. As with leaders in the payments and electronic toll collections, the successful players in this space also kept adding to the conveniences of their digital users by offering F&O investments, thematic investment baskets, wealth portfolios and lending to prevent them from going back to online defaults.

Some digitization initiatives lack one or more ingredients from this template

The difficulty with ABDM (health record digitization), OCEN (credit access digitization) and ONDC (UPI equivalent for digital commerce) is that they lack one or more of these factors.

For example ABDM suffers from not being at an arm’s length from the government. It is too State proximate- being still populated by the staff from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and requires a direct coordination with parallel state bureaucracies (Health is a state subject as per the devolution of powers in the Indian constitution). This prevents it from executing anything at the project level without negotiating (bowing down?) to the whims of 29 separate, state civil service divisions.

As this piece points out, the endemic corruption and inefficiency in direct State controlled departments means that the best plans at the Cabinet level are laid waste when they touch the ground - via the old channel of cronyism in awarding state contracts. There also isn’t any exogenous push or super lucrative incentive from the government to force people and healthcare providers to standardize health records and create a unique central repository for them.

This latter problem, when it comes to financial credit metric aggregation, also plagues OCEN. Add to that, OCEN is still a think tank and advisory body, unlike NPCI. It therefore has little executive agency to carry out its own recommendations, whatever be the elegance of tech it develops.

For ONDC, unfortunately the third constraint prevents its growth, despite very strong institutional structures and likely big moves by the government should the NDA come back to power in 2024.

Commerce is very adjacent to e-commerce and food delivery - where thanks to UPI and growing internet penetration, incumbents are already too big . Flipkart and Amazon makeup 75%+ of India’s ecommerce market. Zomato and Swiggy make up nearly 100% in food delivery. Ditto with Policy Bazaar holding 93% market in online insurance distribution.

It doesn’t work best for them to go on to separate rails to enable offline sellers - of goods or restaurant services - to come online. And without the scale, tech and supply chain integrations that they already have, it will become difficult for merchants/ marketplaces on ONDC to provide a good enough user experience for customers to induce them to switch.

In the next part of this essay, I will talk about the falling Average Transaction Sizes (ATS) in the three large digitized services in India and the implications for firms in this space.