What I read in 2024 - Part 3 of 9

Genghis Khan and George Costanza

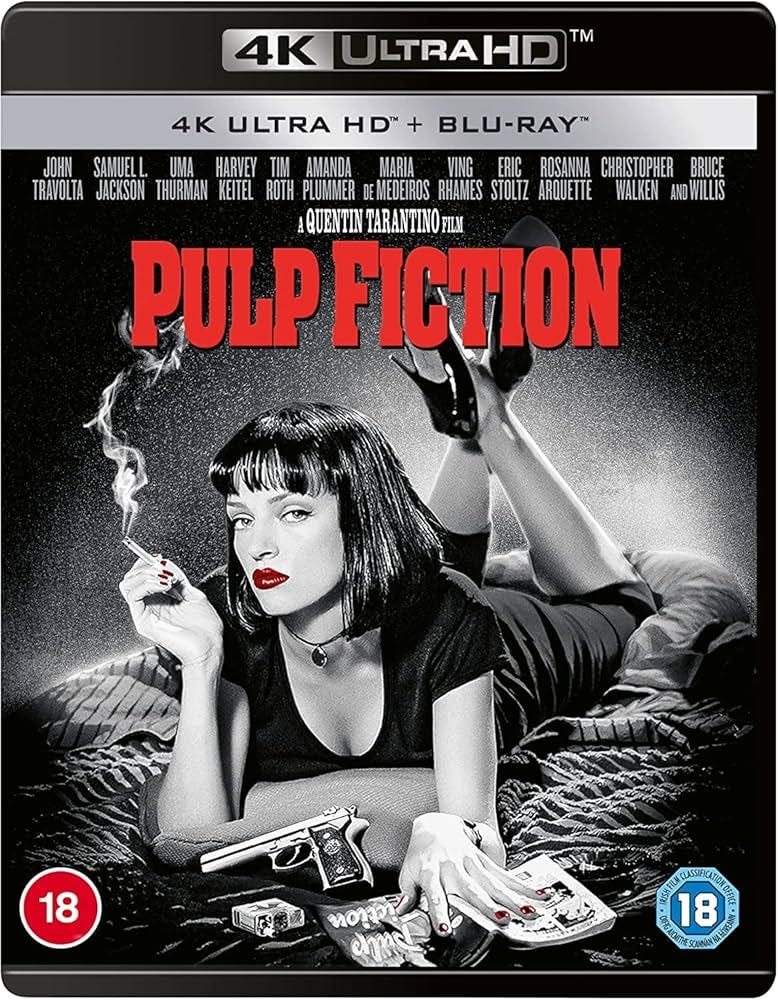

Illustration 1: Pulp Fiction - Meticulously crafted, Immaculately shot and Purposely avoiding a “storyline”. A gift from the ‘90s, to eternity; Source: Amazon Prime

This is the third part of my reading reviews for 2024 (Read the second part here). This part is an analysis of two works of history I read last year. One that provokes a revision in our view of one of the most impactful figures in Medieval History. The other, that does a partial, but pioneering analysis of a decade just gone by.

Illustration 2: Guyuk Khan, Genghis’ grandson, whose two-year reign is famously known for his naive response to Pope Innocent IV’s appeal to desist making war on Christians. Source: The Famous People

This was the boldest, and possibly the most controversial history book that I read last year. “Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World”, written about 20 years ago, is a revised account of the life and times of Genghis Khan and his immediate successors . It adds to the literature around him by considering the perspective of Mongols and their early Muslim subjects in central Asia and Iran.

Until the late 20th century, much of the mainstream discourse around Genghis Khan and his Mongol empire came from European Enlightenment historians - especially those from the aristocratic classes whose ancestors had been singled out and persecuted by the Mongols in their attempts to conquer Europe. When it came to Mongols, European thinkers - from Voltaire onward- found it hard to retain their objectivity around their political and military achievements.

In many ways, Genghis Khan and his hordes were to European historians what Amir Timur, a century later, would become to Indian historians. Both painted as blood thirsty, brutish pagans who were determined to bend or break anything in their path. Europe went even further in the 19th century- with some scientists attributing Down’s Syndrome in children to them having had a droplet of impure Mongol blood in their lineage!

Even the most charitable assessment of Mongols considered them as an alien power emerging from distant lands; opportunistic and clever enough to co-opt the existing ruling classes in Persia and China - as administrators and technocrats - to consolidate an extractive empire. Until the fall of the Soviet Union, which led to the release of a number of native Mongol accounts of their history, this one-sided view of Genghis Khan had prevailed - attributing his success to nothing except psychopathic, grassland barbarism.

There are many reasons why Mongols appear so unreasonable to their contemporaries. Not least because their priors around political power, social organization, economics and diplomacy were entirely different and unfamiliar to the prevailing medieval assumptions around how states and societies should be organized and run. Their right to rule was based on ethnic identity and proximity to Genghis Khan’s bloodline. Not around a religious mandate. Ergo, they allowed a shocking amount of religious tolerance in areas under their control, so long as nobody questioned their authority.

Members of the royal family were allowed to embrace any religion that spoke to them. The upper levels of administration, whether in China or Iran or other parts of Central Asia, were equally diverse in faith.

In an interesting episode, Weatherford talks about the letters sent by the emissaries of Pope Innocent IV to the grandson of Genghis Khan, urging him to accept Christianity and hence stop persecuting Christians. Guyuk, the Khan who was the recipient, finds the premise nonsensical and mildly insulting. In his eyes, he was not waging a war on Christians - but against people who were unwilling to accept him as their suzerain. As for Christianity, anyone was free to embrace it - even some of his queens were practicing Christians.

The Mongol approach to leadership - civil and military- was equally novel for its time. Weatherford’s early account of Genghis Khan’s rise within Mongolia dives extensively into his philosophy of promoting people on the basis of their merit and loyalty to his rule, without regard to their birth.

From Genghis’ master strategist Subutai, born among deer herders, to his grandson Kublai's finance minister Ahmad Fanakati, formerly a slave, the empire’s ranks were full of first-time achievers.

The Mongol eye for talent and their courage to challenge the established social hierarchies paints them as a people far more progressive than any of their time. The corollary to this strategy was a targeted attack on the ruling classes - in Song China, in Khwarazmian Central Asia, in Abbasid Baghdad and under the Princes of Russia. Genghis Khan might not have been as much an enemy of people of Europe and China as of its city dwelling Mandarins and elites - who resisted his new approach to a social order based on merit and an equal application of rule of law. It is also their descendants who persevered and wrote the first, slandering accounts of the Mongols.

In their century and a half of dominance in Eurasia, Mongols accelerated the process of economic exchange that had been halted in the early centuries of the second millennium CE by growing communal polarization between Europe and the Middle East, China’s rising insularity under the Song empire and north India and Central Asia’s political fragmentation after the Ghaznavid and Ghurid invasions.

Ironically, they were able to make this leap because of the backwardness of their economic structure before Genghis Khan took power. Unlike larger economic powers in their neighbourhood - in China, South East Asia, India and Persia which were thriving agricultural centers - Mongols occupational mainstay was barter trade and animal herding. Without an agricultural or allied manufacturing base of their own, Mongol lords became dependent on these subject civilizations for their essentials and luxuries. That need drove their massive investments in transport infrastructure, security, and standardization of currencies, weights, and measures - to ferry goods from one Khan’s lands to that of his cousin as a gift or a tribute. Along these revived routes ideas travelled too - especially those from China which had closed itself for centuries. Things like paper, compasses and gunpowder. Also, Bubonic Plague.

My only criticism of the book is that it oversells Genghis Khan and Mongols. It goes too far in attributing to them the making of the modern world. In my view, the Mongols did experiment successfully with the ideas that would become axiomatic in our modern society - religious tolerance, merit based leadership, an eye for the promises of technology, state support to open trade. But once they vanished, around 1400 CE, these ideas too were lost.

I believe it is a bit ingenuous to shift the credit for Renaissance in Europe from a revival of interest in Greco-Roman philosophy and culture to Mongol enlightenment. Also, one cannot gloss over the massacres that Mongols committed to instill fear among their enemies.

To compare Genghis Khan to a humanist is like stretching revisionism to the point of amusement. This is a book to be taken seriously. But not totally literally. Weatherford shines a light on an unspoken account of Mongol history - their story written by themselves. But to accept everything in here, including the conjectures, would be to take its lessons too far.

Illustration 3: Its Not You, Its Me - George Costanza - an emblem of the Gen X nihilism; Source: Wikisein

I bought this book as a year-end reading list recommendation from the excellent Vivek Kaul . I wonder when his column will be back again…

Chuck Klosterman identifies as one of the hardest things you can be when you choose writing as a career - an essayist. Essayists don’t have a plot to stick to - like novelists do. They also don’t have a mood to recreate - like poets. They just have a blank sheet of paper and a missive to explore a topic - it is like Improv comedy, freestyle dancing. It is not a book that you want to read overnight. It is something you’d like to chew on in pieces, taking in its subtle flavors. Its turns of phrase. Its hidden wit and the visualizations that these words might conjure up if you lived through the 90s.

However, it is the story of the American 90s. Not the ‘90s in India. Most parts of it I have never lived through. To people like us, who came from Tier 2+ cities and went to elite universities in India, the American 90s happened in 2005-10. When I got my first laptop and internet connection, and downloaded episodes of Seinfeld, Friends, music videos of Oasis and Blur- they all seemed to be traveling from a distant galaxy, 10-15 light years away. But the genius of Klosterman is to make you feel nostalgic about a time you never even existed in.

The 90s were a time of Generation X (people born between 1964-81) - that middle child of demography which lay as a buffer state between the contemporary generational struggle between boomers and millennials. Klosterman talks about his cohort here - a generation that didn’t identify with self-righteous outrages.

It was a time when Cosmo Kramer and George Costanza were cool - because they had no career ambitions. And their passivity wasn’t about resistance either. It was a generation that, for better or worse, detested over-analyzing their condition. Since Klosterman himself is one of them, even the book never approaches a grand summation of what the 90s meant. The voice behind the book is content being the least annoying demographic generation. And content with the fact that their time in the world is past.

Because that’s what time does. To me, this unself consciousness in itself was one of the refreshing changes in a time when books are meant to be summarized in bullet points and lessons. Like Pulp Fiction, there are no lessons here. Just well written pages, like flashes of Tarantino’s cinematic quality.

It isn’t too far back, but the world in the 90s, globally, was in a state of “underwhelm”. There was news twice a day. There was a newspaper once a morning. If you had nothing to do on a summer vacation, you often wondered if this is it? If this was all there was to know. People had quirky opinions and superstitions. I remember all the kids writing essays in Middle School about “Andhvishwas” in Hindi. There was a common agreement about certain verifiable scientific facts - like stopping work and not eating during a solar eclipse being a useless holdover from the days when we all believed the earth was flat.

Now it isn’t anymore. Everyone is entitled to their opinions and accorded access to an echo chamber that plays them on a feedback loop. Today we have lost the count of dimensions along which we can be polarized, by half truths and fake news. Compared to those times, conspiracy theories in India and America from the 90s, seem to be like garden variety illnesses of a simpler age.

The point of writing history is, ultimately, to look at events in the past that have had a consequence on the future. In that sense, this book does a fantastic job at foreshadowing what 2010s and 2020s would be like by stopping and looking at the signposts in the 90s. There’s this anxiety of what the internet would be like. Tech guys like Bill Gates talk about it. Talk show hosts laugh them off.

A couple of decades later, the internet truly arrives - a slap in the face of those who dismissed internet culture as a nerdy fad, and the monster in the basement of people like Gates who could never estimate its negative fallout. Might this entire dynamic foreshadow what we are currently discussing about AI. What angels and demons are hidden in our AI future two decades hence!

Then there’s this trial of OJ Simpson, which bookmarks the advent of Reality TV. Henceforth, whatever goes on the TV becomes a TV show. 90s are also when filmmakers like David Lynch anticipate the informal trials of murder victims, with their classic Twin Peaks. Laura Palmer on screen foreshadows Aarushi Talwar in Noida.

In international affairs, this is a time of victor’s complacency - after the fall of the USSR. US dreams of bringing democracy, by encouragement to Russia and China, of a rapprochement with popularly supported governments in Pakistan and Afghanistan. It ends badly - with terrorists flying planes into the twin towers and with China entering the WTO. In the long run, both would be equally fatal to American hegemony.

But not everything that was considered important then goes anywhere. Y2K remains just a false panic. Biosphere2, the expensive scientific facility meant to mimic earth’s colonies on other planets, ends up falling short of its promises and becomes a science museum. The clear craze design ethic - where people liked everything from their phones to their Pepsi transparent - doesn’t last three years.

This isn’t a definitive social history of the 90s. But it comes close to, based on the people I have spoken to, capturing the experience of white American men living in metros quite faithfully.

And it conveys beautifully how different the lived experience was on either side of the Internet and 9/11. And if you lived in India, not more than 25 percent of this mattered to you. But hey, who said no to some fake nostalgia. I haven’t lived in Shire or Westeros either, but I still have vivid memories of it, experienced through books and TV shows.

In the next part of this essay, I go back to fiction. And share my thoughts on the novels that mark the end of a science fiction saga. And a tetralogy set in Peak America.