Is there a template to successful digitization in India? - Part 3

What kinds of market structures arise when an industry digitizes in India? How is the balance of power distributed between digital native firms and legacy firms when this happens?

Back in October 2020, I had this interesting conversation with a senior equity analyst covering fintech stocks across Asia. Ant Financial’s IPO (that never happened) was imminent and everyone was interested in speculating if fintech start-ups in India too would follow the Chinese playbook and the eat banks’, brokerages and asset managers’ lunch, the way Ant had then done in China.

In his reply that now appears to be strongly prescient, he pointed out two things.

First, Chinese fintechs dominance of consumer finance (payments, lending and investments) was a highly path dependent phenomenon - largely driven by the huge gap in understanding the traditional financial sector had accumulated around consumer and SME banking, was a specific result of its intimate relationship with the Communist Party. This was not the case with traditional Indian financial firms.

Second, he posited that India’s digitization had happened a bit later than China, and had offered even the legacy firms the time and templates to digitize their offerings, especially if they were from the private sector. In India , companies that existed before internet in the industries where digitization was rampant, were unlikely to give up their market share to tech-first players.

In this part of the essay, I will try to show how payments, electronic toll collection and brokerage look like post seven years of digitization, in terms of market shares of incumbents.

In the last part of this essay, I have discussed how the income distribution of India limits the Average Transaction Size and marginal revenue per new customer as a business digitizes. That places a severe limit of profitability of the incumbents in each business, with market leaders in all three domains, except one, being loss making.

The question then is what considerations drive them to still expand their business.

If customer acquisition and capture of consumer behavior through digitization is to capture other revenue pools - lending, working capital finance, vehicle loans, fund management and wealth management- then how do these considerations drive offline, legacy leaders and online incumbents in these businesses to compete with each other?

Payments: Tech firms rout traditional banks

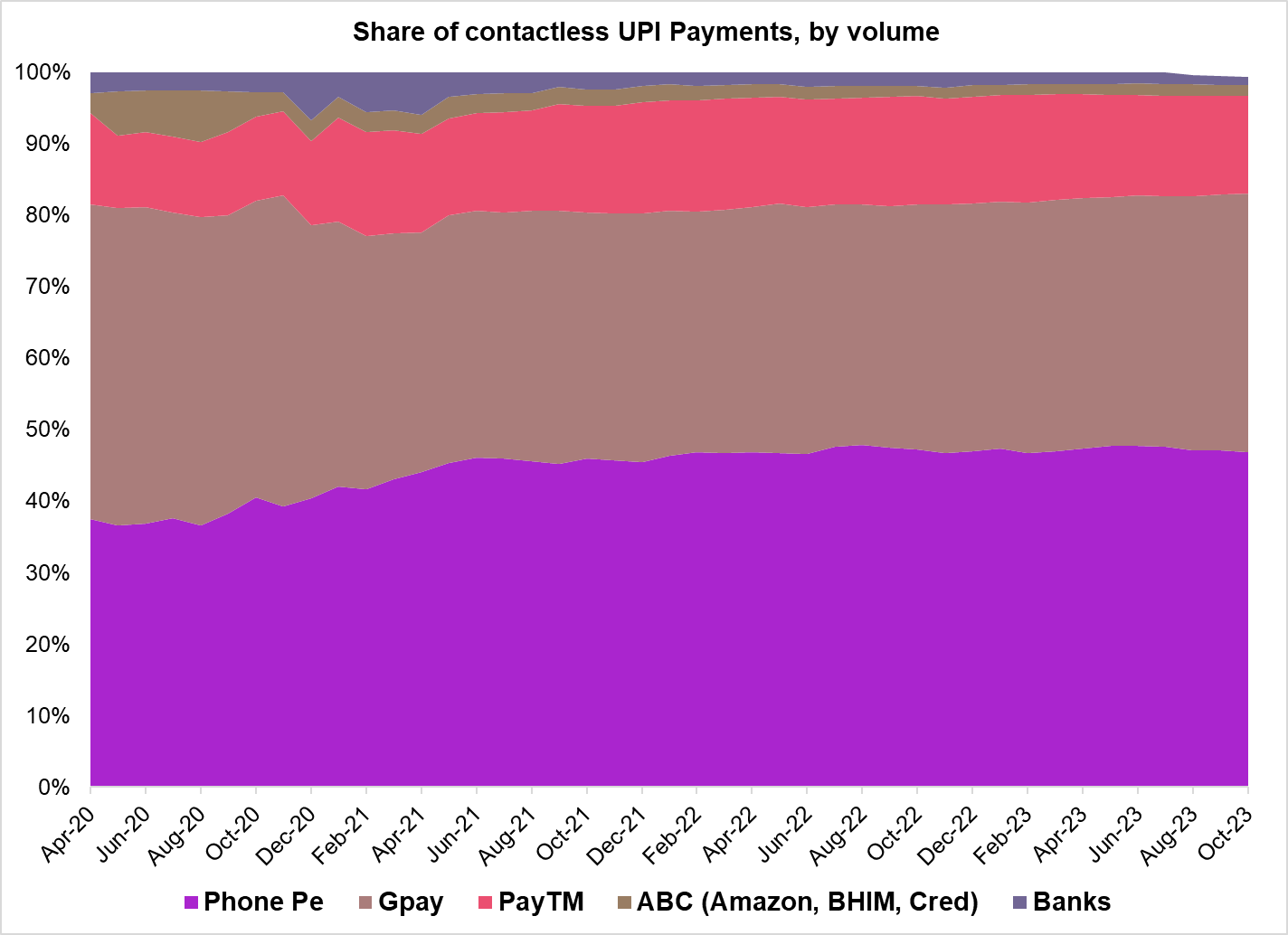

The chart below shows the share of different categories of incumbents in contactless UPI payments space (P2P and P2M UPI payments, Online and Offline QR based payments and UPI 123Pay).

Figure 1: Apps from traditional banks make up a vanishing fraction of UPI payments by volume; Source: NPCI

The share of contactless payments by bank-owned UPI Apps has remained under 3% since 2020. It has fallen under 1.5% since July 2023. UPI Apps owned by Axis Bank and ICICI Bank, though among the top 10 most used by volumes, have effectively taken market shares from AmazonPay and BHIM, even as PhonePe and Gpay have consolidated their positions. In essence, the third party payments app space is effectively a duopoly between the latter two, with PayTM holding a small but significant share. Importantly, all three are non-bank fintechs.

In my previous post here, I had mused on what traditional banks had lost when they allowed non-bank fintechs to own the customer touchpoints through payments and associated behavior. The duopoly in payments has made these fintechs billboards dotting that part of the customer's mind where they make a daily financial decision - of saving, investing and borrowing. It might take several years for payment apps to embed themselves completely into purchasing patterns for financial products. But merge ubiquity with convenience, and at least for low risk financial decisions we might see the needle moving away from banks to PhonePe/ GPay/PayTM. As per my estimate, as of Q2 2023, anywhere between 25-30% of Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) loans were disbursed through PayTM. It has a small share of Personal loan distribution as well (1-2%).

The question then is, why haven’t banks gone harder after gaining market share in UPI-based payments. There are two reasons for it - one is a limitation on their part and the other is a genuine risk assessment.

The limitation comes from our behavior as consumers while making payments. At its heart, making payments is a highly UI/UX centric, winner take all and commoditized business. As someone who has PayTM, GPay and PhonePe apps, I don’t care which one I use as long as its scan-to-pay icon is at a convenient position on my phone screen, it doesn’t “hang” my device and it completes the transaction within seconds. Aside from that, there is little in terms of feature based customer loyalty here. In app analytics terms, these services are meant to minimize on “average time per session” and maximize on “average sessions per user per day”. Ergo, anyone who builds a half decent app, which is parsimonious with data consumption and has a decent user interface wins the game. These are strengths associated with tech-first companies - which PhonePe, GPay and PayTM were, pre-COVID.

By creating a robust tech infrastructure for payments, avoiding any major data security breaches and reducing technical transaction decline rates they have made it tougher for banks to induce their customers to switch away. Add to the fact that they have been consistently adding features like fund and insurance marketplaces, travel and event bookings and bill payments to make their walled gardens more secure.

The other reason is that banks might genuinely be uninterested in the revenue pool that payment apps are looking to intermediate - unsecured personal loans. In the past 1-1.5 years, the share of personal unsecured loans to total new bank credit has nearly doubled from ~12-14% to 23%. Much of this growth has been intermediated by lending tech. Larger banks have been apprehensive of the strictures the RBI could impose on such loans, given the risks they posed to India’s consumption story. They didn’t have to wait for long - in November 2023, the central bank sharply increased the risk weights on unsecured consumer credit for banks and NBFCs.

For banks, while there might be a large underbanked revenue pool out there in consumer credit, which they could tap through getting a better handle at credit eligibility of a customer by understanding their payment behavior, these regulatory costs don’t make it worth their time. In their calculations, RBI is always going to intervene in order to prevent a sharp growth in unsecured credit, keeping this segment a small part of personal loans. The lost opportunity in payments is not worth the fight at the moment.

Toll collection: Banks turn the tables on digital natives

Moving on, let us look at how the playing field has been shaping up for electronic toll payments.

Figure 2: Clearly not a duopoly. Source: NPCI

In the above chart, Non-fintechs include logistics or parking apps (Blackbuck, Park+, etc.) who have an exclusive agreement with banks -IDFC First and Axis Bank- to issue FASTAG sticker linked virtual wallets for storing and paying toll related sums. Other Fintechs include PayTM and Airtel Payments bank. Banks include all licensed commercial banks that issue FASTAG sticker linked virtual wallets.

Two things jump out for me here.

The first, the second-largest players in the ecosystem for NETC toll enablement, which is owning the touchpoints for fleet owners the way PhonePe and GPay have done for UPI payments, are not fintech companies. They are logistics aggregators or parking operators.

Blackbuck’s move into issuing FASTAGs and hence aiming for an entry into the lending tech space by standing as an intermediary between fleet owners within its ecosystem and banks that it partners with, is a good recent example of a company successfully transitioning into a theoretical adjacency. That said, Blackbuck is still not profitable. Unless lending tech helps it pad its bottomline into the black, the jury on the success of this adjacent move will still be out.

The other thing is that banks still hold the greatest share in this market (especially, SBI, ICICI, HDFC and Kotak) maintaining a 45% share in the market, notwithstanding the disruptors. Why have they not been blown away as in payments? Or rather, why have they dug in?

In my view, when it comes to the lending value pool associated with electronic toll collection, banks have a lower hanging and less risky fruit to target.

First, there are economies of scope. Based on the conversations I have had with bankers in this space, it doesn’t make sense for all large, well diversified banks to tie up with tech firms to reach out to vehicle owners. Individual car owners as well as large/mid-sized fleet operators are already likely to have an existing banking relationship with aforementioned market leaders in banking. For these banks then, expanding into FASTAG issuance is simply issuing a FASTAG/NETC enabled wallet to an existing customer.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that FASTAG wallets are a fairly commoditized product - wallets by one bank aren't very different from another in UI/UX sense. This also means that if you are being issued a FASTAG sticker by the bank you are with, there is a fairly low likelihood that you’d want a replacement. In fact, for most large banks, FASTAG isn’t an on-ramp to borrower acquisition, it is just an add-on feature.

Second, even for non-top tier banks in this business, there are fewer trucks, CVs and cars in this country than people owning a UPI-linked bank account, even today. Spending marketing dollars on this smaller TAM, can counter-intuitively, actually be more beneficial. This makes it slightly easier to acquire customers from large banks with aforementioned economies of scope, without getting into exorbitantly pricey fee sharing agreements with tech firms (~70-80 percent share is taken by them).

Especially considering the case of UPI, where millions out of those new customers are from low income cohorts, with a very low chance of applying for a large loan through formal channels. Less loss leading burns in this space then.

Finally, unlike the opportunity in unsecured personal loans being offered in the UPI-based payments domain (even if you sweeten that with fund management and investing opportunities), those for lending in the electronic toll collection world are less riskier. Working capital and vehicular finance to small fleet owners with a verifiable identity makes credit checks less expensive. Their assets can also be collateralized. Much less of a “pie in the sky” then.

A more proximate, less attritional and less riskier opportunity in the toll collection space might have caused the legacy players in banking space to take FASTAG issuance and virtual wallet linkages to it more seriously, leading to a very different - and possibly less oligopolistic market structure.

Brokerage: A stalemate between traditional brokers and digital ones since 2021

Now let us move towards brokerage.

Figure 3: A Leipzig for Banks, not yet the Waterloo; Source: https://www.chittorgarh.com/report/top_20_share_brokers_in_india_by_clients_at_nse/1/?year=2015

The emergent market structure for brokerage looks a hybrid between that for electronic toll collections and UPI-based payments. In the chart above, conventional brokers are defined as pure-play legacy brokerages, which existed before the emergence of digital discount brokers - AngelOne (as Angel Broking), Motilal Oswal, Sharekhan et. al. Digital brokers include discount brokers such as Zerodha, Groww, Upstox and PayTM Money. Bank affiliated brokers include full-service brokers that are partly owned by banking companies - ICICI Direct, HDFC Securities, Kotak Direct etc.

The story that leaps out is of Digital discount brokers’ rise from nowhere in 2015-16 to having a ~55-56% market share at present (in terms of active client accounts). What lies beneath is that since 2021 the shares of digital discount brokers against other incumbents have stabilized. That part of the graph, to me, tells the story of where this market is headed towards.

Much of the context to this story comes from my previous stint at Kristal AI, a Singapore based invest-tech company where I had a chance to work for ~1.5 years. Even in the broking space, where margins on services provided -especially in the FnO segment- are not so cutthroat, the real game is in owning all of the investment touchpoints of an Indian saver.

Based on my experience, Indian investors’ consumer behavior and their preference for what they value from their broker is layered - like a sandwich.

At the bottom of the sandwich are “new to investment” customers. Their monthly disposable savings are anywhere between INR 5K-50K and they are branching out for the first time from real estate, savings accounts and fixed deposits. What they really value is - a fuss-free and easy to understand user interface for investing, a reliable way to transmute money into securities and the other way round, an easy way to liquidate investments and get them credited back into one’s account, plenty of basic investor education/ self explanatory account statements and an ever responsive customer service to address the silliest of queries. This is a game of tech and operational excellence.

The middle of the sandwich is upper middle income and emergent HNIs, who have a few years of acquaintance with markets and depositories. Their monthly disposable savings can range from INR 50K- 500K. They have a robust social security net in place and are looking at financial markets for goal based investing. What they really value is - solid investment advice, standardized and simple products and access to a diverse portfolio of assets in “publicly traded markets”. This is a long game of advisory and risk management abilities, which can not be hyperscaled. Being a simple broker to them “commoditizes” your game, you have to become a broker and advisor.

The upper crust is that of small family offices and HNIs who also avail of your broking services. They don’t have disposable savings, but rather liquid, investable wealth. Beyond everything that the middle and the bottom layers provide, what they are looking for is access and pricing to a genuinely clever suite of financial products, drawn from both public and private markets. It is a long game that requires, aside from broking and advisory, superior access to lending.

The reason for divergence into this sandwich metaphor was to explain why market shares have stabilized in the brokerage business.

Much of the customer acquisition by digital discount brokers in the past seven years, as brokerage digitized, has been in the bottom slice of the sandwich. Their market shares by value are likely to be much smaller than those by customer counts (I estimate Zerodha’s share at ~20%). For a tech first broker, it is easy to race far ahead of its peers in operational and UI excellence, giving it a strong edge in the “new to investment” cohorts. But once you move beyond that, it is a more patient game.

Higher value customers, the likes of which trade with bank affiliated or legacy brokers, have stuck with them because they get a service bigger than just execution. That is why market shares have had a holding pattern in this industry. This is, in a very macro sense, also a reason why digital brokers have aggressively begun to prioritize advisory and fund management verticals within their firms. That said, this is a game that will take longer to be won. Trust based transactions take longer for customers to switch their service providers.

With this, I would like to conclude my 10 part essay looking at patterns of digital diffusion in India. But these are just the preliminary observations and scattered thoughts of one person who thinks that this is an interesting and relevant area of research for all of us. There is only so much one can do alone. So I will invite anyone here to write to me, point me to better sources and studies and share their own personal experiences while being a part of teams which have led this digitization. In the spirit of Advaita philosophy, I close, saying - Neti, Neti (this is not the end, this is not the end).